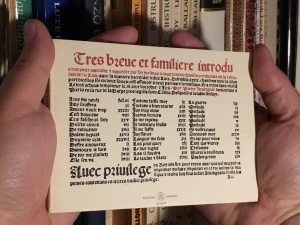

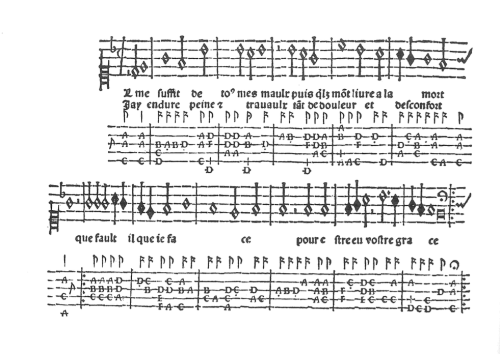

facsimile of Attaingnant’s Tres breue et famílíere introductíon… (1529) by Editions Minkoff, Geneva, 1988 (click to enlarge)

The Lute Part XI

continued from

Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant

In 1529, Pierre Attaingnant published the first book of lute tablature to be issued in France: Tres breue et famílíere introduction pour entendre & apprendre par soy mesmes a iouer toutes chansons reduictes en la tablature du Lutz. (Brief and simple introduction for understanding and learning for oneself how to play any song reduced to tablature for the lute.) Hereafter: Introduction.

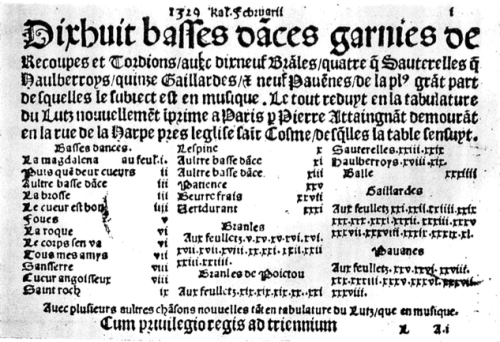

This first volume of lute pieces to be printed in France – a collection of preludes and chansons – was followed less than four months later by a second volume – Dixhuit basses dances: 18 basses dances as well as branles, pavanes, galliards, and other dances in lute tablature.

Together, these two small books comprise the humble beginning of the long tradition of French lute music, which was eventually to dominate the solo lute repertoire throughout the continent. By the middle of the 17th century, “French lute” would represent the apotheosis of refined expression in instrumental music and the repertoire of the French lutenists would in turn influence the fledgling keyboard repertoire… but that’s getting considerably ahead of our story.

PRESS PLAY Attaingnant: Préludes, Chansons & Dances pour Luth by Hopkinson Smith, recorded in 2001. To my knowledge this is the only full-length recording dedicated to the solo lute music from Attaingnant’s prints that has ever been made.

I encountered Attaingnant repeatedly in the early years of my acquaintance with the lute. Diana Poulton includes the Prelude that opens Introduction in Lesson 9 of A Tutor for the Renaissance Lute. I dated this piece June 29, 1994 in my copy of Poulton’s Tutor – the day I began working on it, and that page in my copy is covered with pencilled fingerings. Around the same time I bought Ronn McFarlane’s wonderful CD The Renaissance Lute, which presents a program that surveys the breadth of 16th century lute music and opens with a small “suite” of dances chosen from Dixhuit basses dances.

Around the same time I was taking lute lessons with Pat O’Brien in his midtown Manhattan studio, and at one point he loaned me his copy of Preludes, Chansons and Dances for Lute Published by Pierre Attaingnant, Paris (1529-1530) by Daniel Heartz. All of the pieces for solo lute are included in this important book for lutenists (now long out of print) and are deeply considered by the critical study and then transcribed into modern notation and accompanying tablature. Heartz did not include the 24 chansons Attaingnant set for solo voice with lute accompaniment, as these had already been the published in Chansons au luth, edited by Lionel de La Laurencie, Adrienne Mairy, and Geneviève Thibault and published in 1934.

I copied many songs and dances from the Attaingnant prints out of the Heartz study, and these have been part of the repertoire of lute pieces I play for more than 20 years now.

One of the treasures I brought home with me from my trip to attend The Lute Society of America Summer Seminar West in 1996 was a facsimile of Introduction printed in 1988 by Editions Minkoff in Geneva.

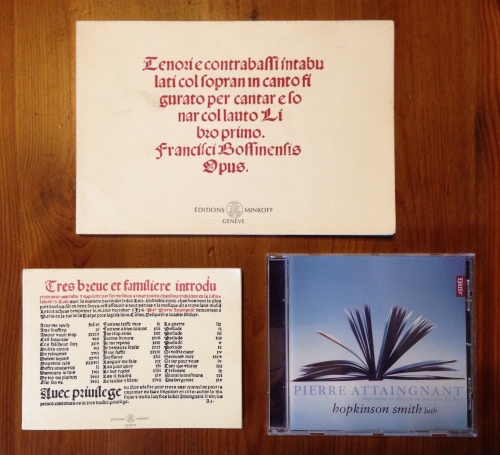

Two facsimiles and a compact disc (clockwise from bottom left): Attaingnant’s Tres breve introduction (1529); Petrucci’s Libro Primo of frottole and ricercare by Bossinensis (1509); Hopkinson Smith’s Attaingnant: Preludes, Chansons, and Danses (2001/2002) ~ click to enlarge

It’s about the size of the palm of my hand. By today’s standards, it’s a very small book: smaller than a mass market paperback and measuring just 15 x 10 cm (about 6 x 4 inches). My facsimile copy might actually be the smallest book I own. The reduced size of some of his books – as well as the labor saved by his single-impression innovation – contributed to Attaingnant’s ability to offer the public printed music at a fraction of the cost of Petrucci’s prints. Paper was an expensive commodity in the early 16th century, and Attaingnant’s lute books were literally half the size of Petrucci’s.

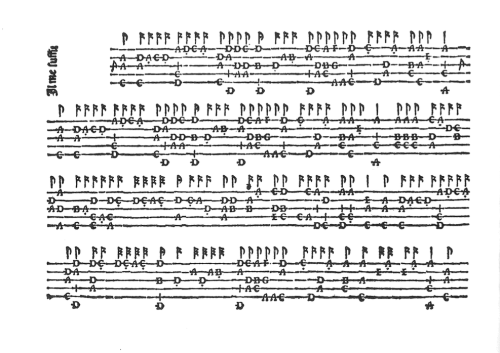

As with Petrucci’s lute books in Italy, Attaingnant’s lute books were the first printed books of instrumental music in France as well as the first printed lute books. He used a tablature with five lines, instead of the six lines used for Italian tablature, and for French tablature issued by subsequent publishers. Introduction is also the only print to use capital letters to represent the notes – Attaingnant switched to lower-case letters in Dixhuit basses dances, which has remained the standard for French tablature to this day. (Another distinction between French tablature and Italian is that the lines depicting the strings of the lute are presented from highest to lowest with the highest string on top – the opposite of Italian tablature, which orders the lines in descending order lowest to highest, mirroring the way the player holds the instrument.)

the title page of Dixhuit basses dances (1530) ~ the unique surviving copies of each of Attaingnant’s lute tablatures are in the Universitäts-bibliothek, Tübingen

Introduction begins with two pages of instructions, and then proceeds immediately to the tablatures. As with Petrucci’s, Attaingnant’s lute books include pieces that represent nearly every genre of renaissance lute music: solo lute fantasies, intabulations, dances, and settings of songs for voice and lute. The notable exception is ensemble music, which is represented by lute duets in Petrucci’s 1507 Spinacino print but absent from Attaingnant’s.

The opening prelude from Attaingnant’s Introduction (1529) ~ 27:29 above on Hopkinson Smith “Pierre Attaingnant” ~ click to enlarge

Preludes and Chansons

Introduction begins with five unnumbered preludes. These were the first pieces to bear this title published in France. Essentially, these five pieces are ricercare composed on Italian models, and Heartz argues that they were chosen to provide short introductory pieces that set up the respective modes for the chanson intabulations that follow – in the same manner set forth in The Capirola Lute Book. There are 34 chansons intabulations in Introduction – but each is set in one of the four modes of the preludes: D, F, C, or G.

More than anything else, Attaingnant was a publisher of chansons (secular songs) and from the late 1520s through the 1540s his presses issued a vast stream of these songs in the new style. The composers of the new Parisian chanson – led by court composers Claudin de Sermisy and Clément Janequin – strove to break away from the more rigidly defined song forms of the previous centuries and the dominance of northern composers as exemplified by Josquin (who is featured so prominently in the Petrucci prints). The primary melody in the Parisian chanson was given to the Superius part (equivalent to the modern Soprano) rather than the Tenor which had been the focus of the chanson in previous centuries. The new style was largely homophonic and influenced by the newly emerging Italian madrigal, similarly seeking to evoke and express imagery depicted in the text of the song.

Il me suffit (Claudin) for lute solo from Introduction (1529) 40:58 ABOVE ON HOPKINSON SMITH “PIERRE ATTAINGNANT” ~ click to enlarge

Claudin’s chansons dominate Attaingnant’s prints and the Introduction is no exception: 23 of the chansons are presented as a lute solo immediately followed by a version for voice and lute (as above Il me suffit). Almost all of the chansons in Introduction had been previously published by Attaingnant in their original four-part choral versions.

Dances

Dixhuit basses dances contains not only the first published dances for lute in France – it was the first volume of dance music of any kind to be published there. The 18 basse dances it contains are intended to be played for what Attaingnant’s contemporaries called the Basse dance Commune (common Basse dance) with a consistent choreography of 20 steps, as opposed to the older, traditional Basse dance “Incommune” which had an irregular choreography, varying the number of steps from dance to dance. The older dance style required music specifically composed for each dance, whereas music composed to accompany the newer “common” style was interchangeable. Like the new Parisian chanson, in the new Basse dance the Superius part took over responsibility from the Tenor for playing the melody.

Music to accompany newer dances popular at court fill out the volume: the branle – danced by a chain or circle of couples – and two new Italian imports, the pavane and galliarde. Also included are two unusual rustic dances titled simply Haulberrroys (22:23 above on Hopkinson Smith “Pierre Attaingnant”): these simple, haunting melodies are my favorites from the collection.

For the most part, the dances are in two parts – the Superius melody above the Bass. They are relatively simpler pieces than the preludes and chanson intabulations, and suitable for beginning lutenists. These were some of the first lute pieces I worked on in my early lessons with Pat O’Brien, when I was learning right hand “thumb under” technique.

P.B.

Despite its title, the Introduction is not structured with any pedagogical plan to lead the beginner from simple to gradually more difficult material. Although none of the pieces in either of Attaingnant’s lute books are of a particularly advanced difficulty, the first prelude (above) is in no way a suitable first piece for a beginner to learn, although some of the dances in Dixhuit basses dances are approachable for the novice. The difficulty – and quality – of the music presented in the two volumes is uneven, and many have thought that the tablatures are a compilation of the work of more than one person. The chansons overall are not particularly attractive or inventive intabulations of their charming originals, and many feel awkward to play.

I personally don’t believe that Attaingnant played the lute. If he had, wouldn’t he have prepared these volumes more carefully? And wouldn’t he have continued to issue books of lute music occasionally over the next twenty years along with the rest of the at least 174 music prints his presses brought forth over the course of his career? Yet he did not – as far as we know, these two small books, surviving in unique copies, are the only lute books he ever printed.

If Attaingnant didn’t play the lute, who made the intabulations and edited the content for the Introduction and Dixhuit basses dances?

Attaingnant did not print composers’ names beside the pieces in his earliest publications, and the two lute books are no exception. Neither contains any indication as to composer, editor, or arranger. That is, no name is at hand unless the initials P.B. attached to fifteen dances in the second tablature can be turned into one.

~ Daniel Heartz

Preludes, Chansons and Dances for Lute

Published by Pierre Attaingnant, Paris (1529-1530), 1964

Heartz identifies P.B. as one Pierre Blondeau, a Parisian musician active in the capital from at least 1506 about whom little is known beyond some records of his work as a singer and scribe in the Sainte-Chapelle and the Chapel Royal, and that he was a “joueurs d’instruments” (instrumentalist). In fact, one of the dances in Dixhuit basses dances is titled Pavane Blondeau. Heartz believes P.B. had a hand in editing the contents of the Introduction, and that it is likely that he collaborated with Attaingnant on subsequent collections of dance music as well, which Heartz deduces from clues in pieces that are duplicated between prints in different instrumentations, yet maintain certain consistencies of style and notation.

Despite the dearth of surviving details about his life, death, family, loves and struggles, Pierre Blondeau is the first French instrumental musician to leave behind any record of both himself and his art – and he did so in the form of a handful of lute pieces.

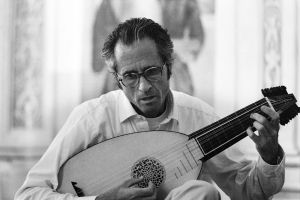

Hopkinson Smith’s “Pierre Attaingnant”

Despite the importance of Attaingnant’s lute books to the history of our instrument, the music from these prints has been almost entirely ignored by lutenist recording artists. I only know of two who have released recordings of any of the Attaingnant lute pieces.

In addition to inclusion on his CD The Renaissance Lute (1994) mentioned above, Ronn McFarlane named his follow up recording of Renaissance dances for lute after one of the pieces in Attaingnant’s second lute book. Between two Hearts (1996) “Puisquen deux cueurs” features two suites of dances compiled from Dixhuit basses dances, alongside dances from other 16th century lutenist composers including Dalza, Capirola, Hans Neusidler, Borrono, and others.

(Since writing this article I have been alerted to three other recordings of music from the Attaingnant lute books: Walter Gerwig (1963), Michael Schaeffer (1968), and Chris Wilson (1995). See Tony Klein’s comment below.)

After decades of focusing primarily on baroque repertoire in his recordings of solo music (with a few exceptions), the American lutenist Hopkinson Smith turned his attention to music from the renaissance after the turn of the millennium, recording a CD of music from the Attaingnant prints in 2001, which was followed by albums featuring music by John Dowland and Francesco da Milano. (For more details see the Discography.)

Pierre Attaingnant: Préludes, Chansons & Dances pour Luth (above) is the only recording dedicated to music from the Attaingnant lute prints that I am familiar with.

There are more than 100 pieces for solo lute in the Attaingnant publications. The few that are known among lutenists today are like gold nuggets glittering on the bed of a mountain stream which catches the eye of the attentive prospector. They may also start a search for what still lies buried further down. Actually, not so very much alchemy is needed to find gold below the surface as well.

Hopkinson Smith

liner notes to “Pierre Attaingnant”

For this recording, Hopkinson Smith performed four of the five preludes and included several intabulations from the Introduction, some which he recast based on their original four-part models. He also composed and/or improvised extended arrangements of several dances, in ways an early 16th century musician may have. The resulting collection is evocative and mesmerizing.

* * *

Although Attaingnant continued to publish books of music at an astounding rate – copies from nearly 160 distinct editions printed after Dixhuit basses dances survive – there were no more books of lute tablature. After he died in late 1551 or early 1552, his widow continued to issue books under the Attaingnant name for a few years, but eventually the firm faded into obscurity.

Attaingnant’s name and the music he printed may have been forgotten by succeeding generations, but the method he pioneered for printing music from a single impression with moveable type became the standard used for printed music for more than 200 years. All of the tablature printed for the lute in the centuries to come would be printed using Attaingnant’s method – by the time Bernhard Christoph Breitkopf introduced new innovations in the mid-18th century, our instrument had fallen almost completely out of use and was deemed obsolete.

* * *

The Lute:

I ~ Meet the Lute

II ~ Francesco da Milano

III ~ The Medieval Lute

IV ~ Petrarch’s Lyre

V ~ Renaissance Lute

VI ~ Baroque Lute (coming soon)

VII ~ Ottaviano Petrucci and the First Printed Lute Books

VIII ~ The Frottolists and the First Lute Songbooks

X ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant

XI ~ Attaingnant’s Lute Books

XII ~ The Lute at the Court of Henry VIII

XIII ~ The Golden Age of English Lute Music

XIV ~ “To Attain So Excellent A Science”: John Dowland, Part I

XV ~ “I Desired To Get Beyond The Seas”: John Dowland, Part II

XVI ~ “An Earnest Desire To Satisfie All”: John Dowland, Part III (coming soon)

XVII ~ Simone Molinaro

XVIII ~ Diana Poulton

Appendices:

iii ~ Lute Recordings:

a ~ Dowland on CD: A Survey of the Solo Lute Recordings: Part I

b ~ Dowland on CD: A Survey of the Solo Lute Recordings: Part II

c ~ Bach on the Lute: 70 Years of Recordings, Part I

d ~ Bach on the Lute: 70 Years of Recordings, Part II (coming soon)

iv ~ John Dowland In His Own Words

v ~ The Lute Society of America Summer Seminar West, 1996

[…] IX ~ Attaingnant’s Lute Books […]

[…] IX ~ Attaingnant’s Lute Books […]

[…] IX ~ Attaingnant’s Lute Books […]

[…] IX ~ Attaingnant’s Lute Books […]

[…] IX ~ Attaingnant’s Lute Books […]

[…] IX ~ Attaingnant’s Lute Books […]

[…] IX ~ Attaingnant’s Lute Books […]

[…] XI ~ Attaingnant’s Lute Books […]

Dear Walter

Fascinating rich article, thanks! If I may correct you on one point: at least three other great lutenists had recorded groups of Attaingnant pieces before Hoppy:

1963 Walter Gerwig

1968 Michael Schaeffer

1995 Chris Wilson.

I have all these records, and they are all worth hearing. In fact I bought the excellent Schaeffer LP “French Lute Music” back in 1968, and I believe it may be the first lute recording with “no nails”, certainly the first such LP. (By the sound of it I think Diana Poulton’s brief 1963 Elizabethan duet recording with David Channon is played with nails.)

Best wishes

Tony Klein

Thank you Tony! I’ve noted this in the body of the article above, as well. I’m looking forward to hunting down these recordings!

[…] XI ~ Attaingnant’s Lute Books […]

[…] XI ~ Attaingnant’s Lute Books […]

[…] XI ~ Attaingnant’s Lute Books […]

[…] piece – Forlorn Hope Fancy – represents Dowland’s work alongside pieces from the Attiaingnant 1530 print, and a broad selection from composers including William Byrd, Hans Judenkünig, Hans Newsidler, […]

[…] XI ~ Attaingnant’s Lute Books […]

[…] XI ~ Attaingnant’s Lute Books […]