Is it not strange that sheep’s guts could hail souls out of men’s bodies?

William Shakespeare

Much Ado About Nothing, 2.3.57-58

The first in a series of posts about the lute.

I would wager that while many, perhaps even most people in our culture have heard of the instrument called the lute and may even know what it looks like, most have never heard one played – either live or on a recording. Yet this paragon of musical instruments, this “instrument of angels” was the most popular instrument in Europe for hundreds of years. Throughout the Renaissance, the lute occupied a position in European society analogous to that of the piano in the nineteenth century. Lute virtuosi played for royalty and popes and were famous throughout the continent, and a rising middle class created demand for the new industry in printed sheet music, providing for music making at home. The art of music took its place at the center of culture on an unprecedented scale. This musical revolution gave birth to the invention of the instruments we use today and intensified the position of music at the heart of both religious and secular ceremonies, while the public and royalty alike acknowledged famous musicians as celebrities and prophets. At the forefront of all this was the lute – a symbol of music’s divine place in human life and the most popular musical instrument of the age.

I didn’t become aware of the lute’s important place in the story of music until I was in my late twenties. I had been studying recorder seriously for a couple of years in the early 1990s and put together a recital with a friend of mine named Mary Guthrie who is a classical guitarist. We played sonatas by Händel and Telemann (she played the continuo transcribed for guitar), we each played some solo pieces, and to fill out the program she asked me to sing some songs by John Dowland (in guitar transcription). It was my first acquaintance with Dowland’s music – or with lute songs in general for that matter – and I was quickly enamored with Dowland’s masterfully crafted miniatures. Shortly afterwards I came across Ronn McFarlane‘s CD The Lute Music of John Dowland at Tower Records, which began my tumble towards the rabbit hole…I was immediately entranced by the sound of the instrument, and began to learn as much about the repertoire as I could.

At this time the internet was still in its infancy and e-commerce as such didn’t exist. Luckily I lived in New York: Tower Records was still around, and there were stores close to the paths I usually travelled. I began to collect recordings by Ronn and other lutenists like Paul O’Dette and Hopkinson Smith, and one day, seeing an old lute in a Manhattan pawn shop, I bought it on impulse. I found Diana Poulton‘s A Tutor for the Renaissance Lute at Patelson’s along with some small collections of easy pieces, and…down the rabbit hole. I was extremely fortunate to soon find myself in the mid-town Manhattan studio of Pat O’Brien, who taught me how to play the lute.

Christopher Morrongiello performs “Lachrimae” (ca. 1590s) by John Dowland (1563–1626), Cambridge University Library manuscript DD.2.11. Filmed in the Chapel from Le Château de la Bastie d’Urfé at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The lute is not really one instrument – it’s a family of instruments. Plucked string instruments with a neck and a body in the shape of a “half pear” have been around in various forms for thousands of years, and are depicted in iconography from throughout the ancient world, as well as existing in analogues in African, Asian, and Middle Eastern cultures. The family of European lutes about which I am writing here emerged in Europe during the medieval period and went through continuous transformation as tastes and styles in music changed over a period

detail from Virgin and child with four angels by Gerard David, Bruges, ca. 1510-15, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Although this was painted in the early 16th century, the angel is holding a 5-course lute from the previous century or older

of roughly 400-500 years from the 14th – 18th centuries. There is some tradition that the lute was brought back to Europe by the crusaders – and although there is scholarly argument about how this came about, the European lute shares many characteristics with the oud, the staple lute family instrument of many Middle Eastern musical cultures. Medieval lutes had 4 or 5 courses – a course is a pair of strings (strung in unison for notes tuned to higher pitches or in octaves for lower pitches) strung adjacent to each other and played together, in the same manner as a contemporary 12-string guitar. The lute appears in iconography as early as the 12th century, and its use spread throughout Europe during the period.

No written music for medieval lute survives (although this hasn’t stopped contemporary performers from trying to reconstruct it or take a stab at what it might have sounded like). During the medieval period the instrument was played with a quill, but towards the end of the 15th century, lutenists began to discard the use of a plectrum and began playing with their fingers, allowing them to play polyphonic music (music with more than one melodic part occurring simultaneously, e.g. counterpoint) which was a predominant style of music throughout the renaissance and baroque periods.

The invention of the printing press around 1440 and the spread of this technology during the second half of the 15th century paved the way for the rise of secular instrumental music in the 16th century, with music for the lute at the forefront of this revolution.

The Renaissance Lute

“There may be, for aught we know, infinite inventions of art, the possibility whereof we should hardly believe if they were fore-reported to us. Had we lived in some rude and remote part of the world, and been told that it is possible, only a hollow piece of wood and the guts of beasts stirred by the fingers of man, to make so sweet and melodious a noise, we should have thought it utterly incredible, yet now that we see and hear it ordinarily done, we make it no wonder.”

~ Bishop Joseph Hall, 1574-1636

For the most part, throughout the 16th century the lute was a 6-course instrument. The highest string, called the chanterelle, was almost always single, and the other courses were double strung. It was tuned in fourths, like a modern guitar, with a major third between the third and fourth courses. From lowest to highest course, a renaissance tenor lute (probably the most common instrument of the family) is tuned: GG – C – F – A – d – g. In the early part of the century it was common to string the lowest three course in octaves (the second and third in unisons), but towards the end of the century some lutenists began to string their courses all in unisons.

guitar, with a major third between the third and fourth courses. From lowest to highest course, a renaissance tenor lute (probably the most common instrument of the family) is tuned: GG – C – F – A – d – g. In the early part of the century it was common to string the lowest three course in octaves (the second and third in unisons), but towards the end of the century some lutenists began to string their courses all in unisons.

Venetian publisher Ottaviano Petrucci produced the first printed book of lute music in 1507, which was followed by a growing flood of printed collections and instruction books over the course of the century in Italy, France, Germany, and England. In Spain, the lute’s counterpart was the flat-backed instrument known as the vihuela (viola de mano in Italy) which was tuned identically, making music for lute or vihuela virtually interchangeable and playable on either instrument.

The lute is constructed almost entirely of wood, and is surprisingly light. Traditionally the only materials besides wood that are used are glue, bone for the nut and gut for the strings. Contemporary players often use modern alternatives to gut for strings – gut is expensive and volatile – but for the last generation or so luthiers have been building instruments modeled on historical originals which adhere to the other traditional aspects of construction. Thin strips of wood are glued together over a mold to make the deep body of a lute – the resonator that gives the instrument its characteristic timbre. Building lutes is an intricate and time-consuming process, and they must be made by hand by a skilled craftsman, hence good instruments are hard to find and most often must be commissioned.

Lute music is written in tablature, a system of notation that depicts where the notes are to be played on the instrument using a composite rhythm notation, rather than the more abstract conventional music notation that depicts pitches. There were three systems of lute tablature in use during the renaissance: Italian, French, and German. Italian tablature (depicted above) uses numbers to denote which fret is to be played, and the six-line “staff” denotes the six courses of the lute, with the lowest course at the top – the tablature mirrors the instrument in the player’s hands.

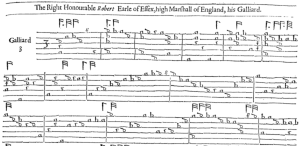

French tablature: The Earle of Essex Galliard by John Dowland from Robert Dowland’s A Varietie of Lute Lessons, 1610. French tablature was used in England and Scotland as well as France

French tablature, which found wider use throughout the continent and eventually supplanted Italian tablature in the 17th century, uses letters instead of numbers and inverts the “staff” with the letters denoting the notes to be played on the chanterelle placed on the top line. Finally, German tablature does away with the use of any lines at all, and uses an extensive set of letters to denote every single fretted note on every string – when the system runs out of Roman letters, it uses Greek letters.

Lutenists today use French tablature as the primary system of notation, while more accomplished players or those with a strong interest in the Italian repertoire (there is a tremendous amount of high quality Italian music for lute) may also be proficient with Italian tablature. Players who can read and play from German tablature are few and far between – most players who want to play German music play from transcriptions into French tablature.

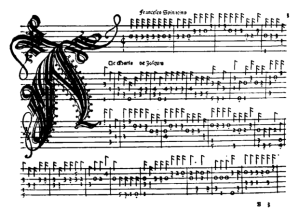

As with the rest of the Renaissance, the Italians led the way. Manuscripts and printed collections of Italian lute music from the 16th century feature music by many, many composers with names like Joanambrosio Dalza, Vincenzo Capirola, Vincenzo Galilei (the father of Galileo), Marco Dall’Aquila, Giovanni Antonio Terzi, Simone Molinaro, and the prolific composer Anonymous (also known as Unattributed) whose works dominate many manuscripts. But towering above them all is the most famous lutenist of the Italian Renaissance – almost unknown today – and the first great instrumental virtuoso of Western art music, Francesco Canova da Milano.

* * *

The Lute:

I ~ Meet the Lute

II ~ Francesco da Milano

III ~ The Medieval Lute

IV ~ Petrarch’s Lyre

V ~ Renaissance Lute

VI ~ Baroque Lute (coming soon)

VII ~ Ottaviano Petrucci and the First Printed Lute Books

VIII ~ The Frottolists and the First Lute Songbooks

X ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant

XII ~ The Lute at the Court of Henry VIII

XIII ~ The Golden Age of English Lute Music

XIV ~ “To Attain So Excellent A Science”: John Dowland, Part I

XV ~ “I Desired To Get Beyond The Seas”: John Dowland, Part II

XVI ~ “An Earnest Desire To Satisfie All”: John Dowland, Part III (coming soon)

XVII ~ Simone Molinaro

XVIII ~ Diana Poulton

Appendices:

iii ~ Lute Recordings:

a ~ Dowland on CD: A Survey of the Solo Lute Recordings: Part I

b ~ Dowland on CD: A Survey of the Solo Lute Recordings: Part II

c ~ Bach on the Lute: 70 Years of Recordings, Part I

d ~ Bach on the Lute: 70 Years of Recordings, Part II (coming soon)

iv ~ John Dowland In His Own Words

v ~ The Lute Society of America Summer Seminar West, 1996

[…] Source: Meet the Lute […]

[…] I ~ Meet the Lute […]

[…] I ~ Meet the Lute […]

[…] “jamming with Eric Clapton” – an apt description of how I felt about it. As I’ve written about here on Off The Podium, it was through listening to Ronn’s recordings that I first fell in love […]

[…] IF you are curious about the lute and the music of John Dowland because a guitarist friend of yours asks you to sing some of his songs, beware. You find Ronn McFarlane’s album The music of John Dowland at Tower Records, take it home and become enchanted. Before you realize what has happened you find you have devoted years of your life to learning to to …* […]

[…] that I own in facsimile copies – I studied these intensely and learned to play from them when I began studying the lute in the early 1990s, including the Margaret Board Lute Book, which contains one of only two known manuscripts thought […]

[…] 1991 release Lute Music of John Dowland (Dorian DOR-90148) was the first lute recording I bought, which I wrote about briefly here in the first article in this series. This CD is high on my list of favorite lute albums. I will […]

[…] never met Diana Poulton, but when I first began to play the lute in the early 1990s, I came across her Tutor and both of her Dowland volumes in the stacks at Patelson’s. At that time I knew absolutely nothing about how to go about learning to play, nor did I know who […]

[…] This morning I was reading Haruki Murakami‘s novel 1Q84, first published in 2009 – 2010. In a passage I came to this morning, two characters are sitting together, drinking herbal tea and having a conversation while listening to a recording of a performance of John Dowland’s Lachrimae. (I was slightly disappointed that Murakami didn’t indicate who was playing it or even mention the lute!) […]

You write so well, Walter. I’d take small issue with one comment underneath the detail from the Gerard David painting. “Although this was painted in the early 16th century, the angel is holding a 5 course lute from the previous century or older.” What this painting shows us is that 5 course lutes were played with a quill in 1510-15. To suggest this is from the previous century or older cannot be evidenced. This lute may have been made the week before the painting was made. In the same way, quill playing seems to have faded, switching to fingers, in the transitional period 1470-1500 on the whole, but there is evidence of quill-played lutes until fairly well into the 16th century, including by Francesco da Milano. The changeover of musical styles is rarely neat and tidy. All the best. Ian

Thank you for this important commentary Ian!