The Lute Part V

In which I offer some observations about the instruments themselves and how they were tuned

If someone finds out that I play the lute, it’s not uncommon to be asked: “oh…what is that?” I’ve even been asked “do you blow it?” once or twice. For non-lutenists – and especially non-musicians – distinctions between this or that lute are esoteric details.

But when one lutenist meets another and they both realize their common pastime (or obsession), often the first question that comes up is: do you play renaissance or baroque?

“There really is no one lute, and each one plays a different literature from a different era.”

Pat O’Brien (1947 – 2014)

…but first, “Medieval Lute”

The European lute repertoire accumulated over a long period of time. Although the extant historical repertoire spans roughly the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, Europeans had already played the lute for hundreds of years before this time period.

The instrument was brought to Europe as early as the 12th century and had proliferated throughout the continent by the 14th. During this time music and technique was transmitted through the aural tradition, and no music written specifically for lute has survived.

detail from the Coronation of the Virgin by Andrea Di Bartolo (1360/70 – 1428) from the Ca d’Oro in Venice (click to enlarge)

But this hasn’t stopped luthiers from building instruments based on lutes in paintings that have survived from the early centuries of lute history, nor has it stopped contemporary lutenists from playing medieval music, in speculative attempts to recreate for modern audiences how medieval music might have sounded on the lute.

The medieval lute was a 4- or 5-course instrument, still closely related to its ancestor the oud, and played with a plectrum.

Contemporary duo Asteria perform medieval song repertoire accompanied by lute; singer and lutenist Eric Redlinger plays an instrument based on medieval iconography. Their beautiful performance notwithstanding, he uses a right-hand technique that belongs to a later era. A medieval lutenist would play with a plectrum, not the fingers, and would not have played more than one musical line as he does here.

Renaissance Lute & The Old Tuning

Mary Magdalene playing a lute by Master of the Female Half Lengths, (c.1490-c.1540) (click to enlarge)

What is generally referred to today as the renaissance lute repertoire spans the period beginning with the tablatures Petrucci printed in Venice in 1507, and ending around the third decade of the 17th century. For most of this time, the lute was a six-course instrument with a single top string, second and third courses strung in unison, and the lowest three courses strung in octaves.

The 16th century saw an explosive growth in the repertoire for the lute in Italy, Germany, France, England, even Scotland. Lute virtuosos published their masterpieces in handsome editions and played for kings, queens, and popes. The rising middle class sought to emulate the nobility and so like them, they also engaged tutors to instruct their sons and daughters.

This was the lute’s “heyday”.

Stringing the six-course lute in octaves on the fourth, fifth, and sixth courses gave the instrument’s sound a fascinating brilliance, and this is part of the allure of the early Italian repertoire (at least for me).

Canon for two lutes by Francesco da Milano

performed by Jean-Marie Poirier & Thierry Meunier

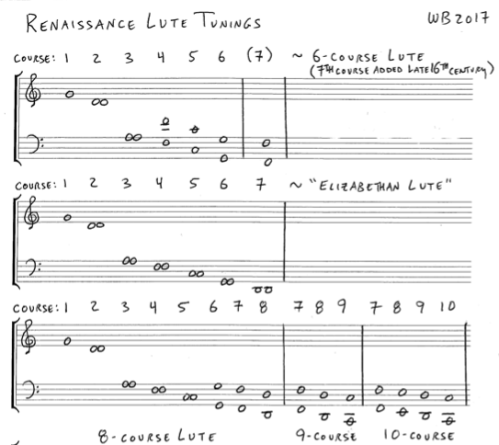

Towards the end of the 16th century, changes in musical style and what the lutenists and lutenist-composers sought to express through their music led to the development of a darker, warmer sounding instrument that expanded the instrument’s lower register, while maintaining the bright, lyrical capabilities of the instrument’s highest courses. Luthiers built instruments with increasingly larger bodies and longer string lengths, and added extra bass courses to the instrument, one at a time: in addition to the vast repertoire for 6-course lute, extant literature exists in varying quantities for 7-course, 8-course, 9-course, and 10-course instruments. The first six courses on all of these lutes were still tuned in fourths with a single exceptional major third between the third and fourth courses. The newly-added bass strings – called diapasons – were tuned as indicated in the chart below.

How to tune a renaissance lute: this is derived from “Important Lute Tunings”, a handout that Pat O’Brien gave me early in my studies with him. These tunings are for a tenor lute tuned in G: today’s “standard”. Lutes were also built in other sizes – treble lutes in C or D, altos in A, and basses a 4th lower than the tenor in D. The tunings above do not represent “standards” but rather indicate general practice for a span of time. Bear in mind that when the lute is concerned, there always seem to be exceptions to general practice. An extremely detailed chart of historical lute tunings may be found here on the website of The Lute Society (UK): the list includes 41 distinct tunings!

This chart is also available in PDF format here.

Another feature of the renaissance lute towards the end of the 16th century was that some lutenists stopped tuning lower courses in octaves, instead tuning every course of the instrument in unison.

Secondly, for on your Bases, in that place which you call the sixt string, or r ut, these Bases must be both of one bignes, yet it hath been a generall custome (although not so much used any where as here in England) to set a small and a great string together, but amongst learned Musitions that custome is left, as irregular to the rules of Musicke.

~ John Dowland

A Varietie of Lute-Lessons (Robert Dowland), 1610

John Dowland (1563 – 1626) was the leading lute virtuoso and lutenist-composer of his time. He wrote somewhat derisively about those who strung their instruments in octaves, describing the ensuing effect as breaking the rules of counterpoint. Nonetheless it appears that both practices – unison and octave stringing – persisted contemporaneously with each other, and that octave stringing of diapasons continued to be a common practice for the duration of the instrument’s historical use: well into the 18th century.

Prelude by Nicholas Vallet (1618)

Tommy Johansson, 10-course lute

Title page of Antoine Francisque’s Le Trésor d’Orphée ~ Paris, Pierre Ballard, 1600 (click to enlarge)

Most lutenists today are not likely to own a collection of lutes that is perfectly matched to every facet of the repertoire he or she plays. A common contemporary practice is for someone who plays renaissance lute to own an 8-course instrument, which will allow the player to play virtually any literature from the 16th century: the first publications for 9-course lute appeared in the first decade of the 17th century, beginning with Antoine Francisque’s Le Trésor d’Orphée (The Treasury of Orpheus), published in Paris by Pierre Ballard in 1600. Note the title nod to our mythical friend, whose name and influence keeps cropping up – not for the last time!

If a lutenist concentrates on a specific repertoire – say, pieces by the early 16th century Italian masters or the 10-course literature – then he or she may have a dedicated instrument that is more ideal for playing that music in particular. But it is not unusual for a lutenist to have as their primary or “workhorse” instrument a compromise – like an 8-course – upon which one could play music from most of the differing styles and schools of renaissance lute music with perhaps not the most authentic historical accuracy, but with a satisfying result nonetheless.

In the early 1600s lutenists in France began to experiment with alternate tunings, and ultimately abandoned the old tuning altogether, settling on a new, standard d minor tuning. Music for “French Lute” – dominated by dances in binary form for the new tuning – soon supplanted the old repertoire for solo lute music throughout the continent and England by the middle of the 17th century, and for the remainder of the lute’s historical repertoire.

Continued in Baroque Lute (coming soon)

The late Pat O’Brien describes and demonstrates the development of the lute family in this brief grand tour of lute history from a pre-concert lecture at the Vancouver Early Music Festival 2006. Thank you, Pat.

* * *

The Lute:

I ~ Meet the Lute

II ~ Francesco da Milano

III ~ The Medieval Lute

IV ~ Petrarch’s Lyre

V ~ Renaissance Lute

VI ~ Baroque Lute (coming soon)

VII ~ Ottaviano Petrucci and the First Printed Lute Books

VIII ~ The Frottolists and the First Lute Songbooks

X ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant

XII ~ The Lute at the Court of Henry VIII

XIII ~ The Golden Age of English Lute Music

XIV ~ “To Attain So Excellent A Science”: John Dowland, Part I

XV ~ “I Desired To Get Beyond The Seas”: John Dowland, Part II

XVI ~ “An Earnest Desire To Satisfie All”: John Dowland, Part III (coming soon)

XVII ~ Simone Molinaro

XVIII ~ Diana Poulton

Appendices:

iii ~ Lute Recordings:

a ~ Dowland on CD: A Survey of the Solo Lute Recordings: Part I

b ~ Dowland on CD: A Survey of the Solo Lute Recordings: Part II

c ~ Bach on the Lute: 70 Years of Recordings, Part I

d ~ Bach on the Lute: 70 Years of Recordings, Part II (coming soon)

iv ~ John Dowland In His Own Words

v ~ The Lute Society of America Summer Seminar West, 1996

[…] V ~ Renaissance Lute […]

[…] V ~ Renaissance Lute […]

[…] V ~ Renaissance Lute […]

[…] V ~ Renaissance Lute […]

[…] V ~ Renaissance Lute […]

[…] V ~ Renaissance Lute […]

[…] V ~ Renaissance Lute […]

[…] V ~ Renaissance Lute […]

Thanks Walter for a nice review. Some comments: That polyphonic playing on the lute wasn´t done until the plectrum was put away seems to be, unfortunately, one of those modern myths that live on, even into our century.

That Dowland was a great composer is certainly true, in our and in the eyes of the renaissance public. However, that he was the leading lute virtuoso is not that easy to support. The Landgraf of Hessen Mauritz, himself an accomplished musician, held Huwet as the prime player of his day. And Reymann, who also must´ve been one of finest lutenists around the turn of that century, also relied on Huwet´s reputation when he wrote his preface.

Thanks Magnus! I really appreciate it when others comment on my articles, I so often learn something new.

I’m not aware of recent scholarship that describes polyphonic lute playing (by a single player) during the medieval period, if you could point me in that direction I’d be grateful.

I have pondered the story of Huwet and Dowland at the court of the Landgraf that Diana Poulton wrote about in her biography of JD many times, and it certainly seems to me that Maurice “damns Dowland with faint praise” in his 1595 letter to Henry Julio of Brunswick:

“…we hold the lutenist Gregorius Hawitten to be an experienced and practiced performer, and as far as madrigals are concerned, his art is unsurpassed. Dulandt, on the other hand, is a good composer.”

He may have had an axe to grind against JD, who was at least a volatile personality and perhaps had other issues as well. When I wrote “leading lute virtuoso and lutenist-composer” I indeed meant in the eyes of the public. Whether or not he was the most accomplished and finest lutenist of his time…I don’t know. JD had a tremendous and far-reaching reputation in his own lifetime that lingered in the collective memory for decades after his death during a period when musical tastes were changing quickly.

[…] V ~ Renaissance Lute […]

[…] V ~ Renaissance Lute […]

[…] V ~ Renaissance Lute […]

I dugg some of you post as I cogitated they were very helpful very helpful

[…] V ~ Renaissance Lute […]

[…] V ~ Renaissance Lute […]

[…] V ~ Renaissance Lute […]