The Lute Part IV

The Lute and the New Humanists

The lute was already well-established as a favorite instrument in Italy by the 14th century (the Trecento). The happy circumstances that led to the rise of the lute as the emblematic and most revered instrument of the European Renaissance can be traced to its being readily on hand for the new humanist philosophers and poets who created the movement.

Already the lute was so familiar that in the early years of the century Dante (1265-1321) had used this simile to describe the counterfeiter Master Adam encountered in the eighth circle of Hell:

Io vidi un, fatto a guisa di lēuto

(I saw one, who would have been shaped like a lute)~ Inferno XXX, 49

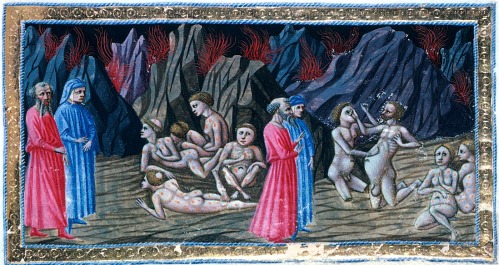

Inferno: Canto XXX by Priamo della Querci (c.1400-1467) ~ surely the potbellied man in the scene on the right is Dante’s Master Adam

But Petrarch actually played the lute, and equating it with the the lyre of Classical Greece, he imbued the cultural perception of the instrument with a rich symbolism that permeated European art, music, and poetry for centuries.

Francesco Petrarca (1304-1374), anglicized Petrarch, who is often called the Father of Humanism, was the Italian scholar and poet of the Trecento whose work inspired the literary revolution known to posterity as “The Renaissance” that quickly brought all aspects of art and culture under its influence. Petrarch’s conceit that the European past since the fall of Rome was a “Dark Age” and a new civilization could be built through a revival of Classical Greek and Roman literature and arts laid the groundwork and inspired the intellectual flowering of the 15th and 16th centuries in not only literature but eventually also art, music, architecture, statesmanship, and nearly every aspect of European culture.

Famously, Petrarch glorified ancient musicians in his writings and poems, and compared himself and his contemporaries to them.

Now if I had so pity-inducing a style

that I could bring my Laura back from Death,

as Orpheus did Eurydice, without rhyme,

then I would live, and be still more happy!Petrarch, Canzona 332 “Mia benigna fortuna e ‘l viver lieto”

translated by Tony Kline

Orpheus ~ decoration by Willy Pogany from The Golden Fleece and the Heroes Who Lived Before Achilles by Padraic Colum, 1921

For Petrarch – and thereafter for the rest of the Renaissance – the lyre of the ancients, the instrument through which Orpheus wove a music so powerful it could move the gods and overcome death, became synonymous with its contemporary equivalent, the lute. The relationship was so strong for Petrarch and his 14th century Italian contemporaries that they used the names for these instruments interchangeably. This identification of the lyre with the lute was so potent and so long-lived in the minds and associations of succeeding generations that as late as the early 17th century Shakespeare could write:

Orpheus with his lute made trees,

And the mountain tops that freeze,

Bow themselves when he did sing:

To his music plants and flowers

Ever sprung; as sun and showers

There had made a lasting spring.

Every thing that heard him play,

Even the billows of the sea,

Hung their heads, and then lay by.

In sweet music is such art,

Killing care and grief of heart

Fall asleep, or hearing, die.William Shakespeare, Henry VIII, 3, 1, 3-14

The lyre had become the lute, and the lute inherited the lyre’s mythical powers as well as its literary associations.

Petrarch is known to have played the lute from contemporary accounts. In his testamentum (his will), he left his buono liuto to his friend Tommasso Bombasio of Ferrara “that he may play upon it, not for the vanity of a fleeting life, but to the praise and glory of the eternal God”. It is generally assumed that many of his poems (canzona is literally ‘song’ in Italian) were intended to be sung, and that he – and others – did so, accompanied on lute.

Like his mentor and friend Petrarch, Giovanni Bocaccio (1314-1375) alluded to and referenced Classical figures and mythical musicians in his poems and other writings. Bocaccio wrote much about music although unlike Petrarch, he was not himself a musician. In his most famous work The Decameron, one of the main characters Dioneo is a lutenist, who accompanies both song and dance throughout the story that frames The Decameron’s 100 tales.

Supper ended, the queen sent for instruments of music, and bade Lauretta lead a dance, while Emilia was to sing a song accompanied by Dioneo on the lute.

Bocaccio, The Decameron, Conclusion to the First Day

* * *

Due to the influence of Petrarch and the poets and philosophers who followed him, the lute became a pervasive emblem of the renaissance and the new humanism. The identification of the lute with ideals believed to derive from great antiquity and the attribution of divine powers to the lute and those who play it were long-lasting. In the centuries that followed, the aspiration to play the lute was held by all who were cultured and it was frequently depicted in the hands of angels and royalty in painting and portraiture.

Minerva presents Apollo (holding a lyre) with portraits of Denis Gaultier and Anne de Chambré in an engraving by Robert Nanteuil from La Rhétorique des Dieux, 1652

Between 1648 and 1652 – three hundred years after Petrarch – a wealthy patron in France named Anne de Chambré compiled a sumptuous manuscript collecting together 56 lute pieces by the Parisian lutenist and composer Denis Gaultier. La Rhétorique des Dieux (The Rhetoric of the Gods) divides the music into twelve sections named after the Greek modes and is replete with mythological symbolism and allegory. Many of the pieces bear titles alluding to Greek mythology and the ancients such as Minerve, Ulisse, Andromède, Mars superbe, Circé, Narcisse, Appolon Orateur… this is considerably ahead of our story! but it serves to illustrate how strong the association was between the lute and the idealized culture of Classical antiquity in the minds of Renaissance Europeans. The lute is a divine instrument.

* * *

The Lute:

I ~ Meet the Lute

II ~ Francesco da Milano

III ~ The Medieval Lute

IV ~ Petrarch’s Lyre

V ~ Renaissance Lute

VI ~ Baroque Lute (coming soon)

VII ~ Ottaviano Petrucci and the First Printed Lute Books

VIII ~ The Frottolists and the First Lute Songbooks

X ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant

XII ~ The Lute at the Court of Henry VIII

XIII ~ The Golden Age of English Lute Music

XIV ~ “To Attain So Excellent A Science”: John Dowland, Part I

XV ~ “I Desired To Get Beyond The Seas”: John Dowland, Part II

XVI ~ “An Earnest Desire To Satisfie All”: John Dowland, Part III (coming soon)

XVII ~ Simone Molinaro

XVIII ~ Diana Poulton

Appendices:

iii ~ Lute Recordings:

a ~ Dowland on CD: A Survey of the Solo Lute Recordings: Part I

b ~ Dowland on CD: A Survey of the Solo Lute Recordings: Part II

c ~ Bach on the Lute: 70 Years of Recordings, Part I

d ~ Bach on the Lute: 70 Years of Recordings, Part II (coming soon)

iv ~ John Dowland In His Own Words

v ~ The Lute Society of America Summer Seminar West, 1996

[…] IV ~ Petrarch’s Lyre […]

[…] IV ~ Petrarch’s Lyre […]

[…] IV ~ Petrarch’s Lyre […]

[…] Although no manuscripts for lute before the 16th century have survived, from the time of Petrarch (1304-1374) the new humanists of the Italian renaissance had established the lute as a central […]

[…] IV ~ Petrarch’s Lyre […]

[…] IV ~ Petrarch’s Lyre […]

[…] IV ~ Petrarch’s Lyre […]

[…] IV ~ Petrarch’s Lyre […]

[…] and politician Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503 – 1542). Sir Thomas the Elder was heavily influenced by Petrarch and is credited with introducing the sonnet to England. It is not known whether he played the […]

[…] IV ~ Petrarch’s Lyre […]

[…] IV ~ Petrarch’s Lyre […]

[…] IV ~ Petrarch’s Lyre […]

[…] IV ~ Petrarch’s Lyre […]