woodcut (of Francesco da Milano?) ~ the cover of Intabolatura di liuto published in Venice in 1536 by Francesco da Forli

The Lute Part II

In one of my first lute lessons with Pat O’Brien (c. 1993) I must have enthused about the music of Francesco da Milano, which I had been listening to on one of the first CDs of lute music I came across at Tower Records, a collection of this composer’s works played by Paul O’Dette that had just been released by Astrée. (This superb recording – still one of my very favorites – is now out of print.)

In what I was to learn was Pat’s typical unrestrained style, he took down two large, thick, heavy, volumes off of the bookshelves that lined the back wall of his studio – or perhaps dug them out from under a pile of other books, I don’t remember – and put them in my hands. This was Arthur Ness’s monumental The Lute Music of Francesco Canova da Milano published by Harvard University Press in 1970, which by then I believe was out of print and generally difficult to come across. American musicologist Arthur Ness is to Francesco like Ludwig von Köchel is to Mozart: Ness was the first to collect all Francesco’s known works from prints and manuscripts found in libraries all across Europe, catalog, and number them. As Mozart’s works are known by their Köchel numbers, Francesco’s extant pieces are known and differentiated by their Ness numbers – especially helpful as more than ninety of them are either untitled or simply named Fantasia or Ricercar in the original sources.

After paging through the books indicating pieces that would be appropriate for me to begin my study of Francesco’s music with, Pat recommended that I transcribe them into French tablature (in Ness’s book they are printed both on the grand staff and in the original Italian tablature notation) and sent me home with both volumes. For the next several weeks in the evenings I sat at the kitchen table, transcribing the pieces Pat had marked – and many others. More than twenty years later, these pieces still form the backbone of my repertoire of 16th century Italian lute music.

After paging through the books indicating pieces that would be appropriate for me to begin my study of Francesco’s music with, Pat recommended that I transcribe them into French tablature (in Ness’s book they are printed both on the grand staff and in the original Italian tablature notation) and sent me home with both volumes. For the next several weeks in the evenings I sat at the kitchen table, transcribing the pieces Pat had marked – and many others. More than twenty years later, these pieces still form the backbone of my repertoire of 16th century Italian lute music.

* * *

Nigel North performs a full recital of Francesco’s music, 2012

Il Divino

Little known today, Francesco da Milano was once the most influential and renowned lutenist in Europe, and in fact Francesco is the first great instrumental virtuoso and composer in the history of Western music. He is first in a long line of composer/performers of instrumental music that includes Mozart and Beethoven – his descendants and heirs – and many others down the centuries, whose music was so powerful and important that it disseminated beyond national boundaries and influenced contemporaries as well as succeeding generations of musicians. His countrymen called him il divino (the divine), the epithet he shared only with his contemporary (painter, sculptor, architect) Michelangelo.

Raphael’s portrait of Pope Leo X with his cousins Giulio de’ Medici – later Pope Clement VII – (l) and Luigi de’ Rossi (r)

Francesco Canova da Milano was born near Milan in 1497. His father Benedetto was also a musician and Francesco was precocious, performing alongside his father in service to Pope Leo X in Rome from 1516-1518, and beginning to draw a regular salary from the Pope in 1519.

Pope Leo X is probably most remembered today as the Pope against whom Martin Luther struggled – Luther published his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517 to protest Leo’s selling of indulgences to raise funds for the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica. The conflict escalated resulting in Leo’s excommunication of Luther in 1521, ushering in the Reformation. Francesco lived in heady times – and he was right there in the thick of it, providing music for the high and mighty and garnering praise for his miraculous lute playing throughout Italy and eventually, all of Europe.

Francesco served three popes in all: Pope Leo X from around 1516 until this pope’s death in 1521, followed by a hiatus from the Vatican during the brief reign of Adrian VI, who was rather more pious than Leo and not a great patron of the arts. By 1524 Francesco had returned to the service of the papacy under Pope Clement VII (like Leo, another de’ Medici) and there are several accounts of his playing in Rome up until 1527, when it is thought that he left the city before the infamous Sack of Rome by the Imperial troops of Charles V (the Holy Roman Emperor) on May 6 of that year.

After some years in Milan and Venice, Francesco returned to Rome by the early 1530s – first in the service of yet another de’ Medici, Cardinal Ippolito – and following the cardinal’s death in 1535, he entered papal service for the third time at the court of Pope Paul III.

The Truce of Nice, 1538 by Taddeo Zuccari – Francis I (l) and Charles V (r) shake hands; Pope Paul III is between them (Click to enlarge)

An illustrious story from this time recounts that Francesco accompanied Paul III to Nice in June 1538, where the pope brokered the Truce of Nice. Francesco played for both Charles V and King Francis I of France (presumably in separate performances, as the two monarchs hated each other so bitterly they refused to be in the same room together). King Francis gave Francesco 225 livres – a small fortune – as a reward, and the account of the transaction in the king’s payment book mysteriously leaves open the possibility that Francesco may have been in the service of Francis I during previous years when it is uncertain where Francesco was employed. The French King was an enthusiastic patron of the arts, and employed many of Francesco’s countrymen including Leonardo da Vinci and lutenist Albert de Rippe.

Shortly after his trip to Nice Francesco returned to Milan where he married Chiara Tizzoni, who gave birth to a son in April 1540. Francesco and Benedetto are recorded as playing in the Pope’s service again in 1541. On January 2, 1543, Francesco da Milano died; the cause of his death is not known. He was 45 years old.

Francesco was buried at the Church of Santa Maria della Scala in Milan, which was demolished in 1777 and is now the site of the opera house known as La Scala.

* * *

woodcut (is it Francesco?) from Intabolatura de leuto de diversi autori published at Milan in 1536 by Giovanni Antonio Casteliono (known today as the casteliono lute book)

Fantasias, Ricercars, Intabulations

Francesco’s surviving works fall roughly into two categories: fantasias or ricercars (named seemingly interchangeably in the sources) and intabulations of vocal works by other composers. The fantasias and ricercars are freely developed counterpoint essays for lute – some more improvisatory in style while others exhibiting a more rigorous formal structure – and the intabulations are arrangements of both sacred and secular vocal works, ranging from faithful, literal translations of these works for lute to some featuring embellishments that depart considerably from the original vocal models. Apparently Francesco was best known to his contemporaries for his intabulations – some musicologists believe the primary reason lutenists discarded the plectrum at the end of the 15th century was to gain the capacity to play the multiple melodic lines of (popular) choral works – whereas it is his fantasias/ricercars that illicit the most interest of lutenists and musicologists today. There also survives a small miscellany of pieces by Francesco, including a canon and a duet for two lutes, and numerous pieces of dubious or uncertain attribution.

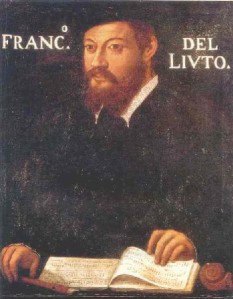

anonymous portrait thought to be Francesco da Milano, c. 1535, now in the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan

Arthur Ness gathered more than 90 fantasias (and ricercars) and about 30 intabulations for his 1970 collection, and more pieces attributed to Francesco have come to light in the last 45 years. As such, Francesco’s is one of the largest bodies of instrumental music to survive from the Renaissance, and his music contains a surprising variety of mood and structure, as well as difficulty – while some of his pieces are approachable to the beginning or intermediate lutenist, others will push the player to the limits of his technique.

The video above is the first of a series of five that together comprise a full recital of music by Francesco da Milano performed by the English lutenist Nigel North in 2012. Nigel concentrates primarily on ricercar and fantasia in his selections here – he plays only two intabulations – including pieces that present a wide variety of emotions – some are light and dancelike while others are more contemplative or even somber. Throughout many of these pieces, Francesco uses imitative counterpoint techniques from the (vocal composition) style of Josquin des Prez (c.1450/1455 – 1521), who was widely regarded as the paragon of composers in the 16th century. Josquin spent time in Milan in the 1480s, and sang in the papal choir at the courts of Popes Innocent VIII and Alexander VI in the 1490s – Francesco was certainly familiar with Josquin’s oeuvre (he intabulated some of Josquin’s motets) and his tenure at the Papal courts brought him into contact with many educated musicians and a broad repertoire of polyphonic music, all of which undoubtedly assisted Francesco in the development of his style,

Francesco’s Legacy

No autograph manuscripts known to be in Francesco’s hand survive, nor records of anything he said, and scant indications of his personality save what may be inferred from his music. No authenticated portraits exist either, although scholars posit several images from early 16th century Italian sources as possible portrayals of Francesco. All of these inevitably are of a bearded man with dark hair, wearing a small cap.

Lute pieces by Francesco da Milano appear as Italian, French, or German tablatures in more than forty printed sources and more than twenty manuscripts from 1536-1603 originating in Italy, France, Germany, Spain, Switzerland, and the Lowlands. Musical tastes and styles changed over the course of the 16th century, and it is a sign of the high esteem in which Francesco’s music and reputation were held that it was still being played and disseminated several generations after his death. In particular, Francesco was at the forefront of the musicians who established the lute as a vehicle for polyphonic composition in the early 16th century of the Italian Renaissance – the Cinquecento – and he was the first to leave behind a substantial body of work as well as an international reputation.

* * *

Over the last twenty years I’ve had fallow periods in which other demands kept my lutes in their cases, sometimes for months at a time. Always it is Francesco’s music I turn to first when I pick up the instrument again – inevitably the first piece I play once I’ve managed to get the thing in tune will be the ricercar Arthur Ness numbered 4, which was one of the first pieces I memorized when I began to play lute. There is an immediacy to Francesco’s music which stills moves and attracts me, a palpable delight in life and music which enlivens many of his pieces, and a depth of expression in some which belies their modest scope (by contemporary standards). It is precious to me that nearly 500 years later, it is possible to play and hear this music from a time and place so different from my own, and feel a connection however tenuous with such a musician.

* * *

The Lute:

I ~ Meet the Lute

II ~ Francesco da Milano

III ~ The Medieval Lute

IV ~ Petrarch’s Lyre

V ~ Renaissance Lute

VI ~ Baroque Lute (coming soon)

VII ~ Ottaviano Petrucci and the First Printed Lute Books

VIII ~ The Frottolists and the First Lute Songbooks

X ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant

XII ~ The Lute at the Court of Henry VIII

XIII ~ The Golden Age of English Lute Music

XIV ~ “To Attain So Excellent A Science”: John Dowland, Part I

XV ~ “I Desired To Get Beyond The Seas”: John Dowland, Part II

XVI ~ “An Earnest Desire To Satisfie All”: John Dowland, Part III (coming soon)

XVII ~ Simone Molinaro

XVIII ~ Diana Poulton

Appendices:

iii ~ Lute Recordings:

a ~ Dowland on CD: A Survey of the Solo Lute Recordings: Part I

b ~ Dowland on CD: A Survey of the Solo Lute Recordings: Part II

c ~ Bach on the Lute: 70 Years of Recordings, Part I

d ~ Bach on the Lute: 70 Years of Recordings, Part II (coming soon)

iv ~ John Dowland In His Own Words

v ~ The Lute Society of America Summer Seminar West, 1996

Great series, Walter. Thank you for taking the time to write this informative, and eloquent post.

Thanks Luis! After spending so much time with Francesco’s music over the years it was wonderful to write about this 🙂

[…] This recital is focused on the early sixteenth-century Italian repertoire: 500 year-old pieces by the first masters of western instrumental music who left behind enough evidence of what they did that twenty-first century musicians can […]

[…] Francesco da Milano […]

Mr. Bittner—

I am working in a slow and careful way through Mr. D Milano’s recercar and thought it would be appropriate to hand a couple of photos of paintings of him on my wall.

Do you have high resolution files of the two Francesco paintings on your page here that you’d be willing to share with me so that a nice printed copy could be made? Thank You for any help.

Cheers

Philip

HI Philip! and what a lovely idea ~ unfortunately I do not have any high resolution photos of the Francesco paintings above. If you find any, please let me know, I would love to have one myself. ~ WB