The Lute Part X

portrait of Francis I of France (1494-1547) c.1530 by Jean Clouet (1475-1540), Louvre Museum, Paris (click to enlarge)

The French Renaissance is sometimes called the “long sixteenth century” by historians to describe a period from the end of the 15th through the beginning of the 17th centuries. During this period, the arts and culture flourished anew as France imported humanism, artistic ideals, and their proponents from Italy and adapted them according to French tastes and aesthetics. In the first half of the 16th century the French King Francis I – François Premier – was a great patrons of the arts and the epitome of the renaissance monarch: a poet himself, it was under his reign (1515 – 1547) that this cultural transformation took place most dramatically.

It was also during the reign of Francis I that the very first printed music books appeared in France – including the first printed lute books.

François Premier

In the 16th century, France was the largest and most powerful country in Europe – although the borders of France then circumscribed a smaller area then than they do today. Many of the grand dramatic events of early 16th century European history revolve around military engagements between France (Francis I), England (Henry VIII) and the Hapsburg Empire under Charles V.

We’ve already read the story about how Francesco da Milano played lute for both Francis I and Charles V in 1538, when Francesco accompanied Pope Paul III to peace negotiations in Nice. Francis generously paid Francesco 225 livres for that gig.

Francis I Receives the Last Breaths of Leonardo da Vinci (1818) by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) (click to enlarge)

In fact, the heavy purse Francis gave Francesco in Nice may have been an attempt by Francis I to lure Il Divino away from the Pope to take employment at the King’s court in Paris. It’s not like this was an isolated incident. Francis I imported many Italian luminaries and brought them back to join his circle and work on his pet projects – most famously, the incomparable Leonardo da Vinci, who entered service with Francis I in 1516 and spent his final years in France, dying there in 1519.

Francis I recruited many other Italian artists including Andrea del Sarto and the Mannerist painters Il Rosso, Giulio Romano, and Primaticcio, who contributed to the sumptuous decoration of many of the King’s extravagant palaces and chateaus.

And he recruited at least one superb Italian musician – the virtuoso lutenist Albert de Rippe (Alberto da Ripa) from Mantua, who joined the French court in 1528 or 1529. Alberto was the King’s most prized lutenist for more than twenty years, and accompanied Francis I to Nice for the summit with Charles V in 1538, where presumably he encountered his countryman and fellow lutenist Francesco.

The High Costs of Early Music Printing

The printing press was pioneered in Europe by the Germans beginning with Gutenberg in the late 1430s. By 1500 there were some million books in print throughout Europe, although printed music – which required a considerable complexity of execution beyond printed text alone – did not begin to appear until 1501 with the editions of Ottaviano Petrucci in Venice. Petrucci’s music prints – treasured by collectors throughout Europe for their great beauty and clarity – set a standard of magnificence that was rarely if ever matched by the work of other music printers in the century to follow.

Adieu mes amours (Josquin) from Harmonice Musices Odhecaton, Petrucci, 1501, Venice (click to enlarge)

But Petrucci’s editions were notoriously expensive. To produce his superlative music books, Petrucci used a triple impression process, running each leaf through the press six times – every printed page receiving separate impressions for staves, words, and notes. It was extremely laborious, running up costs and putting the acquisition of these first editions of printed music in Europe beyond the reach of those without very deep pockets indeed.

It was not until more than a generation later, in Paris, that a printer would bring further innovation to the art of printing music from moveable type, and produce affordable music prints at a volume that could reach a wide circulation.

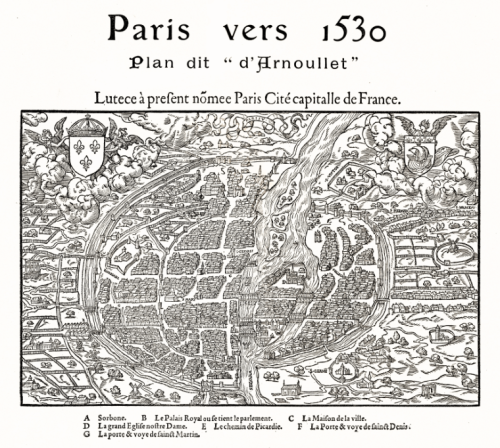

Paris circa 1530, during the reign of King Frances I of France. Originally created by Balthazar Arnoullet in 1550 and reproduced by A. Taride in 1908.

The Golden Age of French Printing

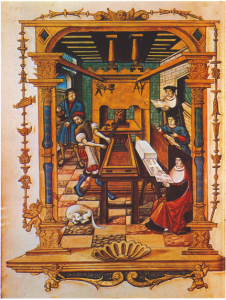

French print shop c. 1530 ~ miniature from “Chant Royal du drapier” MS fr. 1537, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. (click to enlarge)

Paris in the early 16th century was the largest city in Europe, with a population estimated at over 200,000. Johann Heynlin, a German printer, and Guillaume Fichet, rector of the University of Paris, had established the first printing press in France there in 1470, first at the Sorbonne and then on the Rue Saint-Jacques in the heart of the city’s Latin Quarter. By 1500 there were at least sixty presses in operation there, printing books of all kinds. Liturgical texts (especially Books of Hours), classics, histories, books of philosophy, science, law, medicine, biography, plays and stories connected Paris through trade with the rest of Europe through the markets of Northern France, England, Germany, and Italy, fueled the growth of humanism beyond Italy in the early 16th century, and fed the flames of the impending Reformation and Counter-Reformation.

At the forefront of the consumers for books in Paris were the faculty and students of the University, and within a relatively short period of time the printers of Rue Saint-Jacques outpaced the abilities of the traditional scriptoria to meet the demand for books. The King and the nobility too increased the demand for more (and more beautifully executed) books – literary activities were a focus of court life for Francis I and his entourage.

The apogee of French printing coincides very nearly with the reign of Francis I (1515-1547). Badius, Colines, Estienne – these are names that conjure up printing’s finest moment, just as Tory, Garamond, and Grunion betoken excellence in type design, and the name of the collector-diplomat Grolier stands for the ultimate refinement in bookbinding. Under Francis I, Paris succeeded in wresting supremacy in book production from Venice and Basel, the two most influential centers of publication shortly after 1500. It became not only the capital of France in a new and quite modern sense, but also the European “capital of fine book-making.”

~ Daniel Heartz

Pierre Attaingnant, Royal Printer of Music, 1969

Pierre Attaingnant

The man who would revolutionize printed music and develop the technique for its production that would remain the standard practice for the next 200 years arrived on the scene in 1514 – Pierre Attaingnant (c.1494 – 1551/2) is listed in a business contract from January 13 that year as the owner of a press being rented to a Jehan de La Roche.

The American musicologist Daniel Heartz (b. 1928) wrote the book on Attaingnant – actually two books. The first is Preludes, Chansons and Dances for Lute Published by Pierre Attaingnant, Paris (1529-1530) – published in 1964 – a critical study in the tradition of Gombosi’s study of The Capirola Lute Book published a decade earlier (in fact it is dedicated to Gombosi’s memory).

This was followed five years later by Pierre Attaingnant: Royal Printer of Music, for which Heartz personally examined every known print by Attaingnant in libraries and collections across Europe. It’s an astounding and beautiful book, and an exhaustive study and bibliography of the first music printer in France, his influence and legacy, and the early years of the printed music trade.

Although there is little record of Attaingnant’s origins and activities before 1514 – when he appears on the Paris scene already in possession of a printing press – Heartz builds a convincing case on circumstantial evidence for a childhood spent in Douai some 100 miles to the north, in the midst of the musically rich culture of the Low Countries that produced Dufay, Binchois, Tinctoris, Agricola, de la Rue, Josquin…

It seems likely that Attaingnant was sent as an adolescent to study at the Collège de Dainville at the University of Paris – he was a choir boy, and received musical training as part of his studies. He eventually ended up in the print trade, which was located in the same quarter of the city.

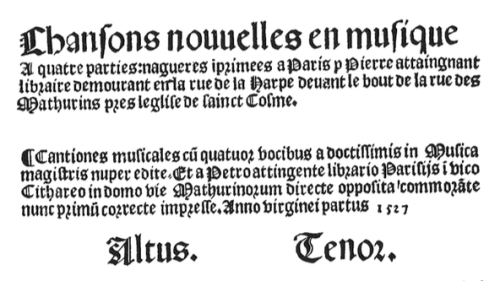

By about 1520 he had married the daughter of a famous Paris printer named Philippe Pigouchet (it’s likely Attaingnant had been Pigouchet’s apprentice) and became his heir. At first he printed liturgical books like so many of the other Paris printers (and he continued to do so throughout his life), but in 1528 he produced Chansons nouvelles en musique, a collection of 31 four-part chansons in the Paris style, more than half of which were written by Claudin de Sermisy (c.1490-1562), the music director of the Royal Chapel.

Chansons nouvelles was revolutionary. It was printed using a single impression method in which a fragment of the lines of the staff are combined on the same piece of type with each note. The type is aligned so that the resulting print gives the impression of a complete staff upon which the notes are printed, although even the most artfully produced books printed this way reveal gaps in the staff between pieces of type.

This short film about 16th century music printing hosted by Donald Burrows, Professor of Music, Open University (U.K.) includes a detailed examination of the press and type pioneered by Attaingnant, and an interesting observation of how printing evolved to imitate handwritten music, then eventually influenced the conventions of how music was written by hand.

This single impression method for printing music – pioneered by Attaingnant – drastically reduced the labor, time, and costs involved in production, and made possible mass production of printed music for the first time. Based on the printing records of his contemporaries and known practice throughout the 16th century, Heartz estimates that Attaingnant produced between 1000 – 1500 copies of each each edition. Attaingnant’s presses brought out at least 174 editions between 1525 and 1558: Heartz suggests a conservative estimate of at least 174,000 books put into circulation.

An English printer named John Rastell (c. 1475 – 1536) is credited as the first to print staff music using a single impression method – two songs printed on broadsides by him have survived that date to around 1523 . But Attaingnant is the first known to have developed single impression printing of music on a grand scale, and his method was quickly imitated and put into practice in printing centers across Europe.

Attaingnant was a publisher – he must have overseen a considerable staff including inkers (those who pulled the press), compositors (those who set the type), apprentices and journeymen, someone to tend to the bookstore…to what extent he served as sole editor and proofreader himself or employed others in this capacity is not known, although the scale of his operation indicates that he would have required help. In addition, Heartz credits Attaingnant with designing and cutting type himself – instead of buying it from a professional punch cutter like his contemporary Claude Garamond. He cites numerous documents from the time that describe Attaingnant as a designer and engraver of type (in addition to all of his other activities) – including the letter from Francis I of June 18, 1531 granting him Royal Privilege.

Royal Printer of Music

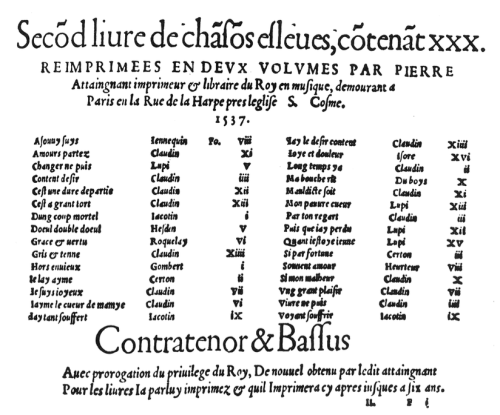

For more than 20 years, Attaingnant issued new books of music at a stupendous rate – as many as 16 in 1534, although fewer on average. His activity as a publisher took place during the period when French presses were converting from the older gothic type (Chansons Nouvelle, above) to the use of roman and italic typefaces (Second Book of Old Chansons, below), and his books reflect this period of transition. Attaingnant no longer used gothic at all after 1542.

Pierre Attaingnant: Second Book of Old Chansons (title page), 1537 ~ Biblioteca del Conservatorio, Florence. This was Attaingnant’s first book to bear the title “imprimeur & libraire du Roy en musique”. (click to enlarge)

Ideas of copyright and intellectual property were in their infancy in the 16th century. The most common approach for a printer to obtain some measure of protection from piracy – from other printers copying their work and in some cases competing with them in their own markets and beyond – was to seek a monopoly or privilege from the monarch, pope, or other authority. Such protection was only as good as far as it could be enforced within the boundaries of the ruler’s domain – usually through litigation. In the case of Attaingnant, the appropriate ruler was the King, and his domain was the largest in Europe.

A bookseller under the auspices of the University of Paris – a libraire juré – received exemption from taxes , a kind of privilege which Attaingnant did not receive at the beginning of his career. When he first began to print books of music in 1528 there was no competition – Attaingnant was the first to print music in France. But he must have seen immediate success, and also the potential that others might wish to profit from it, and sought protection quickly. In October 1529, on the title page of his first book of lute tablature Très brève Introduction his privilege is quoted for the first time, prohibiting anyone else from printing the music Attaingnant has issued for three years. He then applied for and received a second privilege in 1531, extending protection for a period of six years, which he then continued to renew every six years for the rest of his life.

Attaingnant must have met with great success selling his inventory right out of the gate, to be able to bring out new editions nearly every month within a couple years of beginning his enterprise as the first music printer in the Kingdom of France. Presumably not only his music books sold well but achieved recognition at court, because by 1537 he was able to boast of the most coveted honor for a bookseller in France – King’s Printer – on the title page of every book he printed.

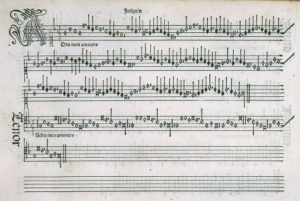

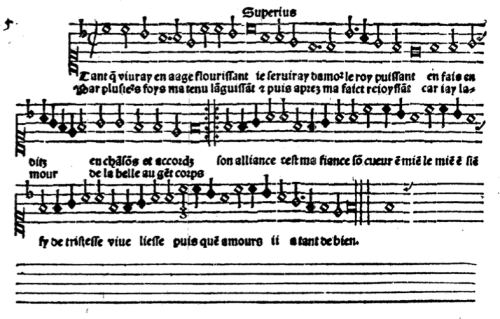

the superius part to “Tant que vivray” (Claudin) from Attaingnant’s Trente et sept chansons musicales a quatre parties, 1531 (click to enlarge)

Over the course of more than twenty years Attaingnant’s presses issued printed music on an unprecedented scale, disseminating (and preserving) the works of 175 composers named in the surviving prints – and music by others who are not named. Next to nothing is known about Attaingnant’s editorial process or about who helped him to prepare all of this music for publication: over 1500 chansons, as well as masses, motets, music in lute and keyboard tablature. From the very beginning of his career it seems clear that he had access to the musicians at the Chapel Royal: the composers whose music features most prominently in his books are Claudin de Sermisy, Pierre Certon, and Clément Janequin – all Royal musicians. Heartz observes that “Nomination as King’s Printer merely made official a situation that existed from the beginning.”

Music for the lute comprised only about 1% of Attaingnant’s output: two books of tablature issued at the beginning of his career, in 1529 and 1530.

A large selection of Attaingnant’s publications are available for free here at the International Music Score Library Petrucci Music Library.

Continued in Attaingnant’s Lute Books (coming soon)

* * *

The Lute:

I ~ Meet the Lute

II ~ Francesco da Milano

III ~ The Medieval Lute

IV ~ Petrarch’s Lyre

V ~ Renaissance Lute

VI ~ Baroque Lute (coming soon)

VII ~ Ottaviano Petrucci and the First Printed Lute Books

VIII ~ The Frottolists and the First Lute Songbooks

X ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant

XII ~ The Lute at the Court of Henry VIII

XIII ~ The Golden Age of English Lute Music

XIV ~ “To Attain So Excellent A Science”: John Dowland, Part I

XV ~ “I Desired To Get Beyond The Seas”: John Dowland, Part II

XVI ~ “An Earnest Desire To Satisfie All”: John Dowland, Part III (coming soon)

XVII ~ Simone Molinaro

XVIII ~ Diana Poulton

Appendices:

iii ~ Lute Recordings:

a ~ Dowland on CD: A Survey of the Solo Lute Recordings: Part I

b ~ Dowland on CD: A Survey of the Solo Lute Recordings: Part II

c ~ Bach on the Lute: 70 Years of Recordings, Part I

d ~ Bach on the Lute: 70 Years of Recordings, Part II (coming soon)

iv ~ John Dowland In His Own Words

v ~ The Lute Society of America Summer Seminar West, 1996

[…] VIII ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant […]

[…] VIII ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant […]

[…] VIII ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant […]

[…] VIII ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant […]

[…] VIII ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant […]

[…] VIII ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant […]

[…] continued from Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant […]

[…] X ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant […]

[…] X ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant […]

[…] X ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant […]

[…] X ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant […]

[…] X ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant […]

[…] X ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant […]

[…] X ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant […]