“I Desired To Get Beyond The Seas”: John Dowland, Part II

The Lute Part XV

continued from

“To Attain So Excellent A Science”: John Dowland, Part I

His Adventures Abroad

I bent my course toward the famous prouinces of Germany, where I found both excellent masters, and most honorable Patrons of musicke: Namely, those two miracles of this age for vertue and magnificence, Henry Julio Duke of Brunswick, and learned Maritius Lantzgraue of Hessen, of whose princely vertues & fauors towards me I can neuer speake sufficiently. Neither can I forget the kindnes of Alexandro Horologio, aright learned master of musicke, seruant to the royall Prince the Lantzgraue of Hessen, & Gregorio Howet, Lutenist to the magnificent Duke of Brunswick, both whom I name as well for their loue to me, as also for their excellency in their faculties.

~ John Dowland

The First Books of Songes or Ayres (1597)

“To Attain So Excellent A Science”: John Dowland, Part I

There is no known attributed portrait of John Dowland. This miniature of an unidentified subject, painted by Isaac Oliver (c1565-1617) now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London was suggested as a possible likeness by Roger Traversac in The Lute Society’s PDF Colour Supplement to LUTE NEWS no. 116, December 2015. “Anno Domini 1590 . . . 27th year of his age” describes this man as the correct age for Dowland, who was born in 1563. (click images to enlarge)

The Lute Part XIV

…happy they that in hell

feel not the world’s despite.~ John Dowland

Flow, my tears

The English musician John Dowland (1563 – 1626) is the central figure in the history of the lute. Composer, lutenist, songwriter, translator, publisher, traveler, academic – four centuries later, Dowland appears larger than life, and in many ways his dreams and accomplishments eclipse those of his contemporaries. Yet Dowland was very much a man of his own time, and his ideals and struggles reflected the concerns, crises, and aspirations of the Elizabethans even as his music expresses universals that resonate deeply with musicians and audiences today.

Bach on the Lute: 70 Years of Recordings, Part I

Smith, Hopkinson, 1981-82/1987. Johann Sebastian Bach: L’œvre de Luth. Auvidis E 7721. AAD (2 CDs) ~ click images to enlarge

The Lute Appendix iii c

Just in time for Sebastian’s birthday (March 21 or 31, depending on your calendar preference): here is an overview of recordings of his music performed on the lute. While perhaps not complete, I believe that the major recordings that have been released on compact disc are described or at least acknowledged here, and many others besides. (Lute performances available on CD are nearly the only recordings considered here.) I trust that members of the lute community won’t hesitate to let me know what I have missed!

Most of the compact disc recordings referred to in this article (and many more besides) are listed in the discography to this series.

Dowland on CD: A Survey of the Solo Lute Recordings: Part II

The Lute Appendix iii b

Continued from

Dowland on CD: A Survey of the Solo Lute Recordings: Part I

(Throughout this appendix,

* indicates a recording I have not heard.)

Dedicated Recitals on Single Discs

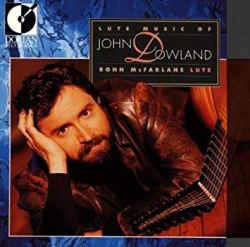

As with the complete editions, three lutenists have recorded entire CDs dedicated to Dowland’s solo lute music:

Dowland on CD: A Survey of the Solo Lute Recordings: Part I

The Lute Appendix iii a

In preparation for my (forthcoming) articles on the life and music of John Dowland for this series, I found myself playing, listening to, and reading about his music more often this year than I have in some time. Coming back to Dowland’s music after any length of time is always refreshing. As my intent this time around is an attempt to regard Melancholy John’s œuvre more comprehensively, I eventually found myself methodically listening to all of the recordings of his music I’ve collected over the years, and hence, the idea for this appendix.

The Lute at the Court of Henry VIII

The Lute Part XII

Unknown Man with Lute by Hans Holbein the younger (1497/8 – 1543), Berlin, Gemäldegalerie ~ American musicologist John Ward speculated that this might be Philip van Wilder, but David Van Edwards has cast doubt on this theory here. (click images to enlarge)

When Henry VIII (1491 – 1547) ascended to the throne of England in 1509, the lute did not play the prominent role in English society and culture it would come to hold by the end of the 16th century. In addition to his matrimonial activities, waging war in France, and reforming the church, it is well known that Henry VIII was an enthusiastic musician, and even composer. He invigorated and developed the musical aspects of life at the English court in the first half of the 16th century far beyond what they had been under previous English monarchs, employing dozens of musicians, including lutenists (or lewters, as they appear in contemporary account books).

Before Henry VIII, the English court was still heavily influenced by Burgundian culture, and use of the harp superseded the lute there until the end of the 15th century. The lute rose to prominence in England by the second half of the 16th century, lagging behind much of the continent by a couple of generations.