The Lute Part VII

He did not compose for lute nor was he known to perform on it, but Ottaviano Petrucci (1466 – 1539) was nonetheless a vital figure in the history of the instrument, and profoundly influenced the course of musical development in the 16th century, and indeed music history in general.

Petrucci was an Italian printer and a pioneer in the publication of music printed from moveable type. In Venice at the very beginning of the Cinquecento, Petrucci produced the first known example of printed polyphonic music: a collection of secular songs titled Harmonice Musices Odhecaton, in 1501.

He also was the first to print instrumental music: several books of lute tablature, produced in 1507 and 1508. Today he is known as the father of modern music printing.

Little is known about Ottaviano Petrucci apart from his professional activities, and I am not aware that any extant images of him exist.

He was born in Fossombrone near Urbino, some 120 miles due south of Venice near the Adriatic coast. Historians assume Petrucci was educated at the elegant humanist court of Guidobaldo da Montefeltro (1472 – 1508) who was Duke of Urbino from 1482 until his death, except for a brief period in 1502-3 when he fled the marauding armies of Cesare Borgia (the inspiration for Machiavelli’s The Prince).

The Ducal Palace, Urbino, where Petrucci is thought to have received his education at the court of Guidobaldo I. Construction of the palace was begun in the mid-15th century. Today a renowned art museum – the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche – it is famous as the setting for conversations from ‘The Book of the Courtier’ by Baldassare Castiglione (published in Venice in 1528) which purportedly took place in the palace’s Hall of Vigils in 1507.

When he was in his mid-twenties Petrucci arrived in Venice, which was then the most advanced center of printing in Italy. Printers in Germany and Italy had begun to apply Gutenberg’s invention to the printing of music by the 1470s, but had so far only produced the relatively simpler notation of Gregorian chant with moveable type.

In 1498 Agostino Barbarigo, the Doge of Venice, granted Petrucci the exclusive right to print music in Venice for twenty years, which he maintained for the full term of the monopoly – no other Venetian printer brought forth any music until 1520.

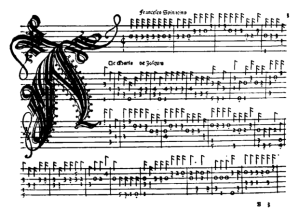

In the first two decades of the 16th century, Petrucci produced dozens of books of printed music across both sacred and secular music genres, at the rate of a new book every few months. He was especially productive between 1501-1509. The first volume printed was the famous Harmonice Musices Odhecaton (One Hundred Songs of Harmonic Music) issued in 1501 – the first example of polyphonic music printed from moveable type. It was edited by Petrus Castellanus, a Dominican friar, and collects 96 secular songs in 3 or 4 parts – mostly French chansons by popular contemporary composers: Josquin, Heinrich Isaac, Johannes Ockeghem, Jacob Obrecht, Alexander Agricola, and others, as well as many anonymous pieces. Petrucci used an unprecedented new technique in which three impressions were made for each page: one for the staves, followed by one for words, and finally one for notes. His books were crafted with painstaking care and are among the most beautiful examples of printed music from the entire 16th century.

The Harmonice Musices Odhecaton and the books that followed began a flood of printed music that revolutionized the distribution of the art form throughout Europe and beyond, and began the process by which studying, performing, and enjoying music no longer remained an exclusive privilege of the nobility, the clergy, and those they patronized, but became a treasured pastime for the middle classes.

Many of Petrucci’s publications were of sacred choral music by masters from the North, as in the Odhecaton. These books contain the first printed editions of many works that are acknowledged monuments of the renaissance choral repertoire: masses and motets by Josquin, Isaac, Obrecht, Agricola, Antoine Brumel, Johannes Ghiselin, Pierre de la Rue, Jean Mouton, and many more. Petrucci is known to have produced 61 publications, of which 5 are lost (there are no known extant copies). In addition to the sacred music that accounts for most of his output, he also published volumes of chansons, frottola, and the first four books of lute tablature ever printed in 1507 and 1508.

Petrucci’s Lute Books

Writing about the Petrucci lute prints, Douglas Alton Smith comments:

It is remarkable that in the first decade of lute music printing one publisher brought out examples of all the major genres of lute music that we know from later periods – intabulations of polyphonic vocal music, instrumental forms such as the ricercar and tastar de corde, solo song accompanied by lute, independent dances, dance suites, and pieces for instrumental ensemble (the lute duet).

~ Douglas Alton Smith

A History of the Lute from Antiquity to the Renaissance, 2002

What is even more remarkable about this comprehensive survey of the various facets of the lute’s repertoire is that with the exception of the lute songs, all other examples are demonstrated in only three of Petrucci’s lute books – alas, one of them, a collection of works by Giovanni Maria Allemani published in 1508, is lost. Unfortunate! Giovanni Maria was one of the most highly regarded lutenists and composers of his time, and worked alongside Francesco da Milano at the court of Pope Leo X.

These books are the first printed books of music for lute – the first printed instrumental music of any kind.

All of Petrucci’s lute books are for six-course lute. He produced two books of lute tablature in 1507: both collections of music by Francesco Spinacino, about whom nearly nothing is known. More than half of the pieces are intabulations of vocal works, most of works that Petrucci had already published by composers like Josquin, Agricola, and Isaac. These 46 arrangements of choral works for lute display considerable variation – some are closer to their original vocal models, but others make free use of diminutions, embellishments, and virtuosic display to an extent that strays far afield. The other pieces in the two volumes include 27 ricercars – a renaissance and early baroque form similar to the later prelude in some cases or fantasia in others – 2 settings of the bassedans tenor of La Spagna (a popular contemporary court dance ), and 6 lute duets. The duets are cast in the style of Pietrobono Bursellis (1417 – 1497) and his 15th century contemporaries, in which the virtuoso lutenist plays the top voice with elaborate scale passages and embellishments accompanied by a second lutenist playing the slower tenor and bass parts.

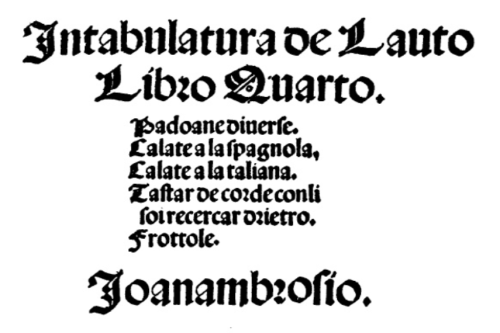

In 1508 Petrucci published the Giovanni Maria Allemani collection now lost, and his Intabulotura de Lauto Libro Quarto, featuring music by Joanambrosio Dalza of Milan. It contains primarily dances, many of which are combined into suites designated either ala venetiana or ala ferrarese. The suites each begin with a pavana (in 4), then a saltarello (in compound meter), and end with a piva (also compound meter, but faster still). I can attest that some of these dances are quite challenging to play! Each suite uses the same or similar melodic material through the changing meters, a long renaissance tradition that can be traced back to the bassedans suites popular at the Burgundian court, whose rulers were great patrons of the arts in the 15th century and influenced aesthetic fashions throughout Europe. This tradition of linked dances exploring the same theme in different meters – increasing in both compression and tempi – reached a full flowering in the lute repertoire at the end of the 16th century in the Pavan & Galliard pairs composed by John Dowland and his contemporaries. They are also among the earliest examples we have of sets of variations as a musical form.

Nigel North performs selections by Dalza from Petrucci’s 1508 print: Tastar de corde; Ricercar dietro; Pavana alla ferrarese; Saltarello alla ferrarese; Piva alla ferrarese ~ Lute Society of America Festival 2014, Case Western University, Cleveland

In addition to dances, the Dalza print includes 5 brief pieces called Tastar de corde (testing the strings), most which serve as preludes or introductions to following ricerare. Dalza’s 9 ricercars display a variety of construction using various compositional techniques, but overall are similar in style to Spinacino’s.

Dalza’s music is challenging and rewarding to study and perform, and although I have rarely heard contemporary lutenists play music by Spinacino, I have often heard them play music by Dalza (and often have been drawn to it myself). We are indebted to Petrucci for preserving these earliest, fine examples of dances composed for the lute from more than 500 years ago.

Petrucci’s extant lute books and a selection of his other publications are available for free here at the world’s largest collection of public domain music: the International Music Score Library Project Petrucci Music Library – which is aptly named for him.

Continued in The Frottolists and the First Lute Songbooks

the colophon to most of Petrucci’s books featured his press-mark: an inverted pear bearing his initials O(ctavianus) P(etrutius) F(lorosemproniensis) under a double cross ~ from the Frottola Libro Primo, 1504

* * *

The Lute:

I ~ Meet the Lute

II ~ Francesco da Milano

III ~ The Medieval Lute

IV ~ Petrarch’s Lyre

V ~ Renaissance Lute

VI ~ Baroque Lute (coming soon)

VII ~ Ottaviano Petrucci and the First Printed Lute Books

VIII ~ The Frottolists and the First Lute Songbooks

X ~ Music Printer to the King: Pierre Attaingnant

XII ~ The Lute at the Court of Henry VIII

XIII ~ The Golden Age of English Lute Music

XIV ~ “To Attain So Excellent A Science”: John Dowland, Part I

XV ~ “I Desired To Get Beyond The Seas”: John Dowland, Part II

XVI ~ “An Earnest Desire To Satisfie All”: John Dowland, Part III (coming soon)

XVII ~ Simone Molinaro

XVIII ~ Diana Poulton

Appendices:

iii ~ Lute Recordings:

a ~ Dowland on CD: A Survey of the Solo Lute Recordings: Part I

b ~ Dowland on CD: A Survey of the Solo Lute Recordings: Part II

c ~ Bach on the Lute: 70 Years of Recordings, Part I

d ~ Bach on the Lute: 70 Years of Recordings, Part II (coming soon)

iv ~ John Dowland In His Own Words

v ~ The Lute Society of America Summer Seminar West, 1996

[…] VI ~ Ottaviano Petrucci and the First Printed Lute Books […]

[…] VI ~ Ottaviano Petrucci and the First Printed Lute Books […]

[…] VI ~ Ottaviano Petrucci and the First Printed Lute Books […]

[…] continued from Ottaviano Petrucci and the First Printed Lute Books […]

[…] they are more substantial compositions – more developed and longer – than those of his predecessors published by Petrucci (Spinacino, Dalza, Bossinensis) They also incorporate a greater use of imitative counterpoint and less reliance on the scale […]

[…] of execution beyond printed text alone – did not begin to appear until 1501 with the editions of Ottaviano Petrucci in Venice. Petrucci’s music prints – treasured by collectors throughout Europe for their great […]

[…] to Attaingnant’s ability to offer the public printed music at a fraction of the cost of Petrucci’s prints. Paper was an expensive commodity in the early 16th century, and Attaingnant’s lute books […]

[…] is generally referred to today as the renaissance lute repertoire spans the period beginning with the tablatures Petrucci printed in Venice in 1507, and ending around the third decade of the 17th century. For most of this time, the lute was a […]

[…] VII ~ Ottaviano Petrucci and the First Printed Lute Books […]

[…] VII ~ Ottaviano Petrucci and the First Printed Lute Books […]

[…] VII ~ Ottaviano Petrucci and the First Printed Lute Books […]

[…] I hold in my own hands, and took the time and care to write down some of the music they created, in some cases went to the tremendous effort it took to print it, and somehow against all odds (especially in the majority of cases in which only a single copy was […]

[…] VII ~ Ottaviano Petrucci and the First Printed Lute Books […]