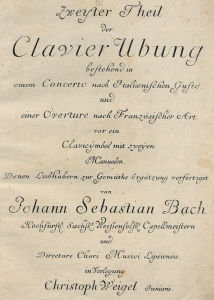

In 1735, when Sebastian was 50 years old, he published his second volume of keyboard works, Clavier-Übung II (“Keyboard Practice II”). It contains two pieces for double-manual harpsichord: Concerto nach Italienischen Gusto (Concerto in the Italian taste, now known at the Italian Concerto, BWV 971), and Ouvertüre nach Französischer Art (Overture in the French Style, or simply the French Overture, BWV 831).

That Sebastian chose to pair these two works in the same publication paid homage to the old tradition (by his time) for composers to seek a harmonious way (or perhaps take sides) between the perceived opposition of French and Italian musical styles – an argument that had been carried on in European musical circles for centuries. This discussion is a part of Sebastian’s œuvre too, and was influenced by the work of his contemporary François Couperin (1668-1733) and his “les Goûts réunis” or “reunited tastes”, which was published in 1724. Although Sebastian and Couperin never met, they corresponded with each other. The subjects of their letters has long been a tantalizing mystery to Bach scholars, as the letters were subsequently used as lids for jam pots and thus destroyed. Since Couperin had died two years before Clavier-Übung II was published, it is possible that in his own way, Sebastian also intended the volume as an homage to Couperin himself – or as a rebuttal or commentary on the various merits of each style .

Title page of Clavier Ubung II by Johann Sebastian Bach, first edition, 1735 (click images to enlarge)

The Italian Concerto and the French Overture are, in many ways, “opposed” works and very different from each other. To begin with, they are set in keys as diametrically opposite as possible: the concerto is set in the sunny, joyful key of F Major, whereas the overture resides a tritone away in the deeply serious key – for Sebastian – of B minor: the same key in which he set his monumental Latin Mass. It is significant that the original version of the overture was in C minor, and that Sebastian transposed it down a half-step for publication (ostensibly for theoretical reasons).

Another way in which these works differ profoundly is in relation to other works in Sebastian’s catalog. The French Overture is the longest keyboard suite that Sebastian ever wrote. It has eight movements, for the most part in binary form, and takes about a half hour to perform. The overture is ordered in the instrumental suite form invented and developed by French lutenists in the previous century, that had long since been taken up by the harpsichordists and other composers. But it is only one – albeit the grandest – among many. Sebastian wrote many of these “French Suites”, including 6 Partitas, 6 “English” Suites, and even 6 “French” Suites for keyboard; 6 Cello Suites; 3 Partitas for violin; 4 Orchestral Suites : all of these are suites in the French style.

The Italian Concerto, however, stands alone. It is unique among Sebastian’s compositions: a concerto in the Italian style for solo keyboard, without orchestra.

Sebastian, Vivaldi, and Corelli

disputed portrait of our friend Sebastian by Johann Ernst Rentsch the Elder (d. 1723) painted c. 1715, which would make him 30 years old here.

Sebastian had a broad curiosity about the music of his time, and he composed music in virtually every format except opera – an argument can even be made that his Passions, with their intrinsically dramatic nature, are unstaged operas in all but name. So it’s no surprise that Sebastian made a serious study of the Italian concerto form – which was wildly popular in the early 18th century – and that it deeply influenced his own style and many of his compositions.

From 1708 – 1717 Sebastian worked for Duke Johann Ernst III in Weimar, initially as organist, and later assuming responsibilities as Konzertmeister for the court in 1714. It was his second stint in Weimar (he had worked there for 7 months in 1703). This time, he worked and lived there from when he was 23 until he was 32, his first wife Maria Barbara bore their first 6 children there (3 who survived including including William Friedemann and Carol Philipp Emanuel), and the composition work he began there would have serious repercussions for the rest of this career: preludes and fugues that would eventually be compiled into The Well-Tempered Clavier, the beginnings of the Little Organ Book, and a number of cantatas.

In addition, while Sebastian was at Weimar, the Italian violin virtuoso and composer Antonio Vivaldi’s first collection of concerti for string instruments L’estro armonica, Op. 3 (The Harmonic Inspiration) was published in Amsterdam in 1711. Vivaldi’s star was ascendent in European musical circles, and his music was popular at Duke Ernst’s court. Over a year between the summers of 1713 – 1714, Sebastian transcribed at least 4 concerti from L’estro armonica for solo keyboard, as well as other concerti by Vivaldi, the Marcello brothers, Telemann, and others. In 1950, Sebastian’s known concerto transcriptions for solo keyboard were collected into the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis (BWV catalog) by Wolfgang Schmieder as BWV 973-987. The Italian Concerto was assigned to BWV 972.

(There are also 5 concerto transcriptions for organ from the same period, BWV 592-596. Three of them are of concerti by Vivaldi.)

Concerto Op. 3, No. 9 in D Major RV 230 from L’estro armonica by Antonio Vivaldi, performed by Fabio Biondi and Europa Galante.

Sebastian’s transcription of Vivaldi’s Concerto Op. 3, No. 9 in D Major RV 230 from L’estro armonica for solo keyboard, performed on harpsichord by Sophie Yates.

Years later, when Sebastian composed his own concerti at Köthen and Leipzig, he used Vivaldi’s symmetrical Venetian concerto style as a template, rather than the popular concerto grosso style of Arcangelo Corelli (1653 – 1713). Corelli’s famous Opus 6 collection of 12 Concerti Grosso were published posthumously in 1714 – while Sebastian was in Weimar. He was certainly familiar with Corelli’s music – his Fugue on a theme by Corelli, BWV 579 is based on the subject of the second movement of the Sonate da Chiesa Op.3 – No.4 in B Minor .

Corelli’s music was immensely influential throughout the 18th century: Händel used Corelli’s concerti as the model for his own Opus 6 Concerti Grosso, and Corelli’s works were still being published and performed long after Vivaldi’s name had languished into obscurity. But it was the simpler, more streamlined three-movement scheme of Vivaldi that Sebastian exploited when he began to write his own concerti – the renowned Brandenburg Concerti in 1721, and the bulk of his concerto catalog that dates from the 1730s. Sebastian retains the dramatic contrasts between solo and ensemble developed so skillfully by the Italian masters, and injects the form with his own compositional obsession, counterpoint.

The Italian Concerto is one of the most performed and recorded of Sebastian’s keyboard works. One of the earliest and most admired recordings is this one by the inimitable Wanda Landowska in 1935 and 1936. Although not a “historical” harpsichord performance by any stretch of the imagination, the verve and energy in her interpretation is palpable.

Hybrid Music: the Sonate auf Concertenart

When Sebastian composed the Italian Concerto, did he cast a look back over the transcriptions he had made in Weimar twenty years earlier, and decide to try his hand at writing a concerto for keyboard alone that wasn’t an adaptation of an existing composition for soloist and orchestra? The unaccompanied concerto was not a standard genre in the 18th century. It’s a very unusual piece.

Perhaps no musical works fascinate us more deeply than those speaking in multiple tongues, for music that refers to more than one style or genre not only poses a conceptual challenge to the listener, but also invites a number of intriguing historical and aesthetic questions. Were these multiple levels of meaning intended by the composer and perceived by early audiences? If so, how might they have subverted the so-called generic contract between composer and listener, whereby the two tacitly agree on which gestures and patterns signify a particular genre? To what extent did a given work redefine its type? What concerns prompted the composer’s mixing of styles or genres?

~ Steven Zohn

Music for a Mixed Taste

Style, Genre, and Meaning in Telemann’s Instrumental Works, p. 283

The Sonate auf Concertenart (concerto sonata, or sonata in concerto style) was a term coined by the 18th century music critic Johann Adolph Scheibe (1708 – 1776) to describe a chamber work that strays beyond boundaries audiences might expect in terms of structure and virtuosity. Scheibe is the only one known to have used the term. The concerto sonata does not, strictly speaking, constitute a substantial genre in its own right: rather, it refers to a handful of compositions that expand and develop the sonata genre by incorporating elements from the concerto genre. The Italian Concerto stands as the epitome of this kind of composition. Other examples of the concerto sonata include Sebastian’s Sonata in A Major for flute and harpsichord obligato, BWV 1032 and a few works by early 18th century composers in Thuringia and Saxony including Johan Christian Schickhart, the lutenist Adam Falckenhagen, Johann Mattias Leffloth, and Georg Philipp Telemann.

This thrilling performance of the Italian Concerto by the remarkable French harpsichordist Céline Frisch is representative of a contemporary, historically informed approach and much more likely to illustrate the piece as Sebastian originally envisioned it than Landowska’s recording (above). Note how Frisch uses the varying timbres of the double manual instrument to imitate the contrasts between soloist and orchestra in a concerto: “tutti” passages are played on both manuals coupled together, while “solo” passages are played on the front 8′ choir (upper manual), often accompanied by the left hand tutti on the lower manual.

Steven Zohn (quoted above) goes on to summarize Scheibe’s discussion of the hybrid form:

…a sonata in concerto style may have three, rather than the usual four movements (presumably in imitation of concertos); one upper voice that is ” worked out more fully than the other” that is, an instrument assuming the role of soloist and accordingly playing contrasting and perhaps virtuosic figurations (“convoluted, running, and varied passages”); and a bass line that is less concise than those in “regular” sonatas.

~ Steven Zohn, ibid.

All of these qualities describe the Italian Concerto. Its three movements follow the Venetian concerto model, the vigorous outer movements in ritornello form framing a slower, more introspective second movement. The “one upper voice” played by the right hand is quite “fully worked out” and to describe the left hand passages in the outer movements as “less concise” than is usual would be a gross understatement: these are as “fully worked out” and challenging to play as the right hand passages are. The Italian Concerto is a bravura, virtuosic tour de force.

If the exuberant display of the outer movements show off Sebastian’s ability to present as grand a conception of the concerto as anyone, it is the intricate, touching aria that he placed between them that reveals his true temper.

To my ear, among Sebastian’s other works for solo keyboard it is Variation 13 from The Goldberg Variations – which were published 6 years later as Clavier Ubung IV – that most closely resembles the Andante from the Italian Concerto. Both feature a florid solo in the right hand above two parts in the left: altogether comprising a three-part texture in 3/4 time. The left hand part of the Andante alternates relentlessly between two repeated notes in the bass and a restless series of four rising or falling thirds, over which the right hand sings, soars, and plunges. But whereas Goldberg Variation 13 resides in the clear and uplifting key of G Major, the Andante is set in D minor, and exploits some of the lowest notes on the instrument through long passages featuring implied pedal tone. The effect is deeply serious and emotionally touching, and reveals Sebastian at his most intimate even in the midst of one of his most extroverted works for solo keyboard. For the deeply religious Sebastian, his compositions in three parts are often intentional reflections, meditations, or appeals to the Trinity, the three-part nature of the Christian God, and it is this aspect of Sebastian’s personality that comes through in this movement, despite the apparently secular mood of the concerto.

Although Sebastian composed the Italian Concerto for double manual harpsichord, it is through performances on the modern piano that most listeners are likely to encounter it today. Here András Schiff performs the Italian Concerto at the Bachfest Leipzig, June 11, 2010.

* * *

Our Friend Sebastian:

The Italian Concerto

Bach on the Lute: 70 Years of Recordings, Part I

Sebastian’s Music in Nashville:

[…] The Italian Concerto […]

[…] The Italian Concerto […]

[…] The Italian Concerto […]

[…] The Italian Concerto […]

[…] The Italian Concerto […]

[…] The Italian Concerto […]

[…] The Italian Concerto […]

[…] on Cantata BWV 39 with Portara & the Nashville Concerto Orchestra, and I will also perform the Italian Concerto on solo […]

[…] 1. The Italian Concerto […]

[…] The Italian Concerto […]